How director and producer Paulette Randall’s career flourished, from Rose Bruford and Theatre of Black Women to ‘Tin Star’, the Spotlight Prize and the 2012 Olympic Games.

Not many directors can say they’ve worked on an opening ceremony for the Olympics, but this is just one feather in the fascinating and colourful cap that Paulette Randall wears. She has been on both sides of the camera – starting as an actor at drama school and creating her own theatre company, to developing a spectacular career as a producer and director for both stage and screen and being awarded an MBE in the 2015 Queen’s Birthday Honours List for her services to drama.

Her credits include Waterloo Road, EastEnders, Tin Star, Death in Paradise, Kerching!, Doctor Faustus, Love Letters to the NHS, Rudy’s Rare Records, Funny Black Women on the Edge, The Wives and many more.

We’re delighted that Paulette will be returning as the Screen Director for the Spotlight Prize 2024 and had the chance to ask her about the evolution of her career, her top tips for performers, and her hopes for the future of the performing arts. Here’s what she shared:

“If you know that this is not something that you want to do, it’s something that you need to do, then that will make all the difference.”

Hi, Paulette! How did you first get started in the industry?

I got started in this mad, crazy industry [by going] straight to drama school at the age of 18 from school. A friend bet me a fiver I wouldn’t apply to this particular drama school. It was Rose Bruford. They were doing the Community Theatre Arts course, which I don’t think they do anymore, and I read it and thought, “Oh, this sounds quite interesting. It’s not just a straightforward acting thing,” because I didn’t really [act], apart from messing about at school doing the old school play and stuff. So that’s how I got in.

What made you decide to transition from acting to directing and producing?

“I knew that I was supposed to be in that world. I just didn’t know what my role was going to be.”

I spent three years training, but I did a lot of devising and improvisational work as well. So that was great. It wasn’t all text-based, so it made it easier to think about it in a different way. And then also – I think after the first year – I remember one of my tutors saying to me, “Paulette, you seem to be here in body, but not in spirit.” And I said, “Well, actually I’m a bit bored. I don’t know if I’m supposed to be here.”

But I knew that I was supposed to be in that world. I just didn’t know what my role was going to be. I knew I felt comfortable within that environment of being creative, so I suppose it was inevitable that I would go and look elsewhere to see what else I could do under that umbrella of being in the arts.

They used to do the Young Writers’ Festival at the Royal Court, and one particular year I’d written a play and it was submitted for the competition. Your prize was a professional production of an extract of your play, and my play was being done at the Theatre Upstairs. At the time, I was watching the director and thinking, “Oh.” At first, I was walking around going, “Oh, I’m a writer now. My play’s on at the Royal Court.” And then I just got into watching what he was doing, and before I knew it, I said to him, “Do you know what? I want to do what you do.” And he said, “Well, you have to talk to Max.” Max Stafford-Clark was the artistic director at the time. And the director of my extract was Danny Boyle, who was running the Theatre Upstairs then.

He said, “Speak to Max,” so I did – a lot! And for quite a while, because at first, he said, “No, you trained as an actress and now you’re writing, and now you say you want to direct? You’ve got to choose!” And I said, “What if I want to do all of them? What about that, Max?” And he was like, “No, no, no, no, no, you have to choose.” I got on his nerves, actually, until I broke him and he said, “Okay, you can come as my assistant.” So I ended up training at the Court for about a year and a half – maybe two years.

Even when I was at drama school, I knew there were people there that were so much better than me and also had a real yearning for it and an understanding of it, because I do think actors are quite unique. I think they’re extraordinary human beings. I’m not one of them. I don’t understand how they do what they do, but I’m glad they do because that means that I can do what I do and what I love.

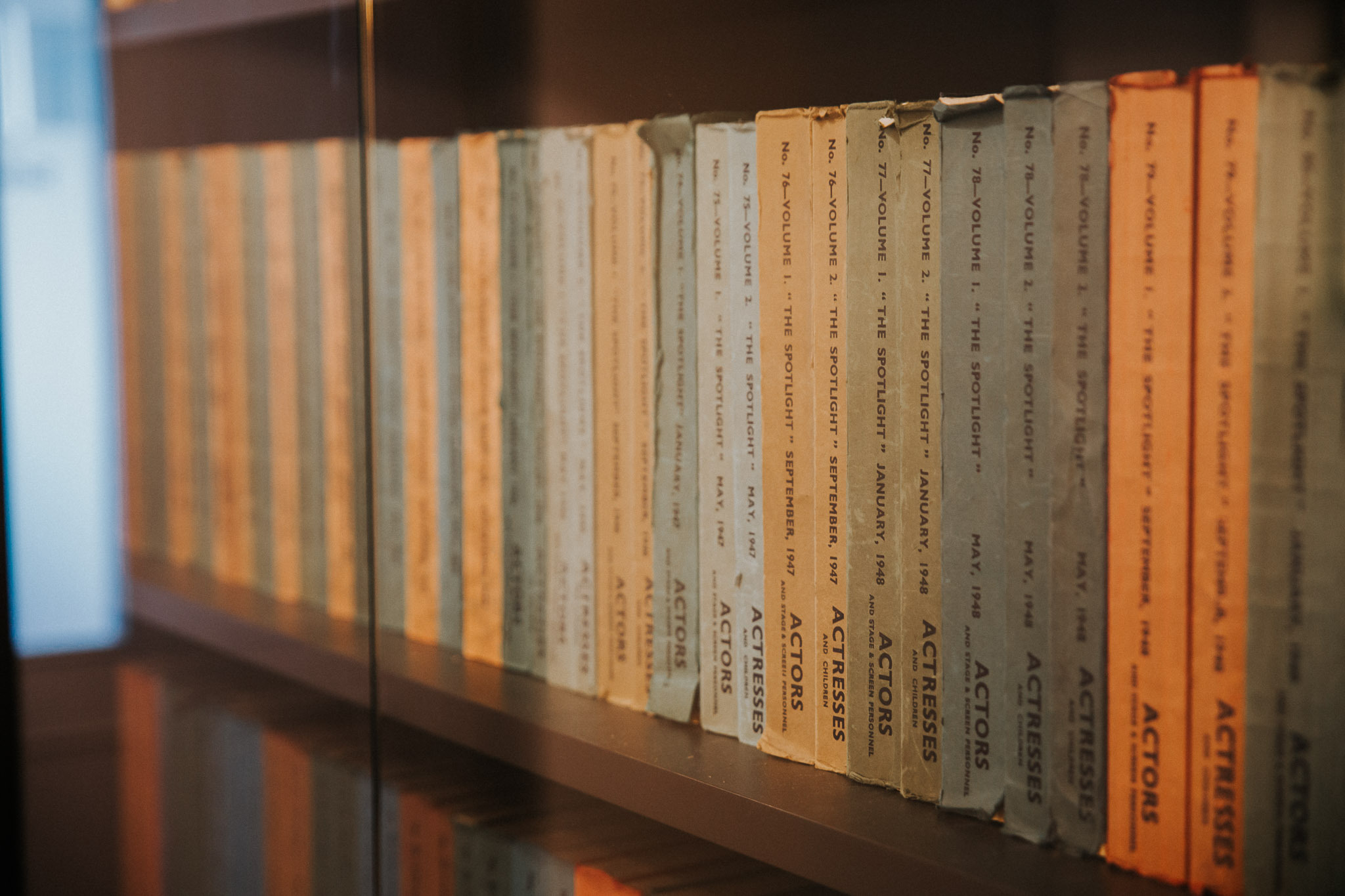

You started your own company – Theatre of Black Women – in 1982. Could you tell us about that process?

I think it was when we were at drama school. We were aware that, at that time, it felt like if you were going to pursue acting as an option in life, most of the roles that were out there for young Black women were just a nurse or an unmarried mother – something that just didn’t appeal to us. We had done so many different and varied things at drama school that allowed you to think bigger and wider and deeper, so we decided that instead of just going into the industry and doing whatever, we’d set up our own company and write and perform our own stuff. So that’s what we did. Hence, Theatre of Black Women.

We had no idea how to set up a company or anything like that, but we knew that we needed to get some money in or we needed to pay ourselves. So we did workshops for young women up and down [and] all over London, and then we rehearsed at night. If the desire is there to do it, you’re going to find a way. As the company continued to grow, I left. But Patricia (Hilaire) became brilliant at administration because that’s what was needed, and also, she had a feeling and yearning for that as well. And Bernie (Bernardine Evaristo) kept writing and performing. So we just kind of grew and morphed.

Because you are in the arts, I think that there’s always going to be barriers. But it was interesting at that time, because, politically, I think we were in quite a unique situation. There were so many companies in London: Black and Asian women, Gay Sweatshop – there were so many alternatives that, when I think about it now, it was quite a golden period really. So yes, there was adversity, but that was part of the reason for doing it – because you felt that it wasn’t equal. And so you wanted to make sure that your voice was heard and that you were making some kind of impact and making a change and, hopefully, affecting people in a major and positive way.

You co-directed the opening ceremony for the London Olympics in 2012. Can you tell us more about that experience?

So you know I said to you years ago, when I trained at the Royal Court, Danny Boyle was my director? When I started training at the Royal Court, I ended up assisting Max. I was primarily his assistant, but I also assisted Danny on a show that we did Upstairs called Panic. Cut to 30 years later, he phones me and says, “I don’t suppose you know what I’m doing.” And I said, “Yeah, everybody knows what you’re doing. What do you want?” Anyway, it turns out it was that, and he wanted an associate – someone to work with him in order to make it all come together.

The funny thing is, none of us had ever done it before. We knew we were going to put on a show and all of us – Danny, myself, Mark, Suttirat (Anne Larlarb), the designers, Stephen Daldry – we all come from a theatre background. So that was the one thing that we had in common and we understood – we know how to tell a story. So it was just about telling the story on a bigger scale. You get all of these people that have these skills that can come in and help you tell the story that you want to tell. So with our writer, Frank Cottrell-Boyce, and the team that Danny put together, it was basically a team of storytellers.

The major, major thing was the volunteers, because without them, you can’t do anything like that. But they were so committed, so they just became our actors. And that’s what the joy of it was – seeing these people growing from the person that came in, that was really shy, to being able to stand on a platform like that and perform. Extraordinary.

How does directing for screen differ from directing for stage?

Well, obviously there’s a technical aspect to cameras [and] screen. I’d say I’m still enjoying my journey of learning how, what they can do and why, but there’s a bit of me that’s really not interested. What I’m really interested in is what the actors do. Primarily, I’m looking for that element that’s going to tell the story and that’s going to engage us and move us in some way. So as long as whatever the camera’s doing is going to enhance, help, support – do all of that – then I’m happy.

I’m learning more about size and all of those technical things. At first, I was like, “Oh no, I’m not interested. I can barely turn the TV on. I’m a Luddite.” But now I’m beginning to understand it more. I get a little bit more excited each time I do some TV work, because I went into it without any training.

I got the opportunity to direct drama for TV without having been to film school or anything like that. Lots of people said to me, “Well, how come you did it?”

For a start, I’ve been directing for so long, but also, I’d had experience in television from another side. I’d worked as a script editor and then went on to become a producer, so I understood how you make television from that angle. And I knew how the floor works – stuff like that.

So that wasn’t alien to me, but what was was literally going behind the camera and saying, “Cut,” and things like that, which was just fantastic and exciting. I love what I do. Ultimately, I’m doing the same thing: I’m telling a story and I’m working with these amazing people who help us to tell the story.

What have been the highlights of your career so far?

It’s hard to answer that. The opening ceremony was such a one-off and so unique, so I don’t know if it was the highlight. I used to say to people if they say to me, “What’s your favourite show?” it’d be the one that I’ve just done, or the one that I’m about to do that I don’t even know what that is yet.

Directing Tim Roth in Tin Star was just a laugh. We had a great time. We met at school, Tim and I, and when I got the job, we hadn’t been in touch for years. But anyway, when I got the job, he sent me a text saying, “Oh, I hear you’re going to be my boss, and apparently I can be difficult.” So I just sent him a text back saying, “I’m not a stroll in the park either, so brace yourself.” So we just had a laugh. It was a bit like being back in the sixth form common room. It was very funny and he was fantastic.

A lot of people don’t know that Tim and I, individually, were in touch with our old drama teacher, a woman called Jill Walker. And so Tim said to me – they used to call me Paul at school – he went, “Paul, should we get Jill to come and see what we’re doing?” I went, “Too right, yeah.” And so she came – can you imagine? So for her, there’s me behind the camera, Jill standing beside me, Tim’s acting over there. It was just a surreal and brilliant thing to happen. So moments like that, because it’s all about life and love between that eclectic group of people.

How do producers, directors and casting directors all work together to find the right actor for the role?

In all honesty, it depends on where you are in not just your experience, but in terms of how the industry sees you. There are certain directors, and it doesn’t matter who’s casting it, if they don’t want those actors, then that actor’s not going to be in it. When you are lower down the hierarchy, sometimes you don’t get any say in who the actor is because it will ultimately be decided by the producers. So it really does depend on who you are, where you are in your career, and what your producers are like.

Most of them will say, of course, that they want to be open and generous and take into consideration your thoughts and your feelings. So you have to try all the time, saying to them, “I have to be in the room,” or, “I have to be on the floor with that person.” That’s the difference.

Also, we are now in an age which I find slightly annoying, where it’s all about getting a name instead of just getting an actor. So that’s really quite hard to fight because they say, “We won’t get greenlit, no one will come and see it.” It’s not true! We did Doctor Faustus at The Globe I can’t remember how many years ago, and didn’t have names in it, but we had such a cracking cast, we completely sold out the run. It was just wonderful because you go, this is a great team of actors. They’re not the big names that everyone’s going, “Oh God, well, I’ll go and see them.” It was just, “Oh, they’ve got them. Oh, oh, who’s that? Oh, I didn’t know they did that.” It was far more interesting and intriguing and it worked.

What would be your number one piece of advice for performers?

“Whatever it is that makes you you, hold onto that, develop it, nurture it, love it. Because that is what is going to make the difference every time you walk into a room.”

If you know that this is not something that you want to do, it’s something that you need to do, then that will make all the difference. Because it’s a mindset, because there’s going to be so many things that will be obstacles that just make you have to really work for it. You have to really, really want it because it’s so difficult. Why do I think that you are going to be great and not that other person? What is it? That’s the difference.

Sometimes it’s just a connection that happens in the room. You’ve all got this unique thing, otherwise I’d work in animation. I love the fact that you are all unique. So whatever it is that makes you you, hold onto that, develop it, nurture it, love it. Because that is what is going to make the difference every time you walk into a room. I know, I hate the self-taping thing. And I understood it with Covid and lockdown and all that.

Once we started going back to work, you go with anything that’s going to make it possible, but it’s so difficult. I think we probably have to try and hold onto that old-fashioned thing of saying to people, “Please, come and see me. If I’m doing something in a pub theatre, please, come and see me.” Because that will make all the difference.

I’ve met people and I’ve got time to spend with them in front of the camera and they’ve been prepared and they still get nervous, and they could still come across as, “I don’t know if I’d want to work with you.” My job is to make sure that everybody wants to work with you, so I’ve got to see you at your best and at your most comfortable and confident. Sometimes, when you’re at home, you’re so nervous because you don’t know if the lighting’s right, did you remember the lines? There’s also nobody giving you feedback.

But my feedback is my personal take on what you’re doing. Some other director will go, “Oh no, why would she say that?” But it’s nice to have that feedback because, as an actor, a lot of what you do is instinctive. It’s about playing and it’s about finding that truth and that thing that makes it spark.

This is your fourth year directing the Spotlight Prize for screen. What do you enjoy most about this?

I couldn’t believe it! I said, “Are you sure you want me back?” I’ve loved it. Again, because I’m meeting all these amazing graduates and I think what an exciting moment in your life. You’re making that transition from having spent three years, four years, training and now you get the opportunity to go, “I’m coming. World, you better be ready for me.” So I’m thrilled to be part of that journey. It’s very, very exciting.

They’re all completely unique and different and wonderful. And for me, it’s really exciting because it’s about the future and that’s crucial. I’m not playing a part, but I’m kind of experiencing a bit of what the future could look like and involving those people. So it’s just the best.

If you could change one thing about the industry, what would it be?

“”Paulette, you’ll never be taken seriously as a director until you’ve done a Shakespeare.” But why not? Because that’s some sort of benchmark? I think we have to get rid of those things.”

I don’t think I’d change one thing. I think I’d change quite a few things. I think I’d change the access to the arts. I’d have to make that far more open and freer. Yes, of course I’ve worked with people who’ve trained, I’ve worked with people that haven’t trained. It’s not about the training necessarily, because you can learn so much. When you go to drama school you get all these skills and it’s amazing. And you get this wealth of knowledge about the world that you’re going to be working in and the plays that you can do and all of that and it’s wonderful.

But if you can’t act, you can’t act. No one can teach you that. They can enhance what you’ve got and they can make it fabulous and develop it and help you nurture it and grow it. But they can’t fundamentally teach you how to act. But I still think that there’s got to be ways that we can make the industry more user-friendly.

I think that it’s still class bound in a lot of ways. I remember when people said to me, years ago, “Paulette, you’ll never be taken seriously as a director until you’ve done a Shakespeare.” But why not? Why wouldn’t someone take me seriously? Oh, because that’s some sort of benchmark? I think we have to get rid of those things.

Ultimately, we’re storytellers, so let’s get better at doing that and let’s develop our skills and all of that. But don’t tell me that I can’t be because I haven’t done one particular genre of the arts. It’s about freeing this up more.

And the whole thing with size and what’s considered beautiful – I’m so tired of that! I won’t name any names, but I’ve had producers who, when I’ve suggested a female actor for a part, say, “Oh, she’s not really beautiful,” and I can’t even begin to respond to that. For me, it’s so disgusting. So there’s so many things that I’d want to change.

Finally, what would be your dream production to direct or produce, or who would be your dream actor to work with?

Dream production? I don’t know. I think there’s a couple of shows that I’ve done in the past that I think, “Oh, I should do that again because I think I’d do it even better.” One was a play called Pecong, which was a Caribbean version of Medea, which was very, very funny and very rude, and then very dark. I’d love to do that again.

People? I mean, you sometimes go, “Well, who would I like to work with?” I don’t know – I don’t think I’ve met them yet. I’d work with anybody. That’s the thing. I would love to work with anyone who wants to join me to tell the story in a particular way. When you have those meetings with actors and you start talking about, “What do you get from the play and what do you think?” And when you hear from someone and you think, “Oh, their thoughts are quite good. Oh, actually I wasn’t thinking about that. Oh, that’s good.” I get excited and I think I want to be in a room with you and I want to share your ideas and your passion for telling the story.

I don’t think I could honestly say to you a name because that’s not what gets me going. I want to work with people who are brilliant and passionate about what they do. You could have been doing it for 150 years, or you’ve just started. That’s what excites me.

There was one. Okay, so one of the first shows that I assisted on had Tracey Ullman, Ron Cook, Alan Rickman and Leslee Udwin. And I remember, Alan Rickman, every time I saw him after that, he would always stop me and say, “Paulette, how’s it going? What’s happening with you?” How beautiful a human being was he? Throughout my life, I could have seen him anywhere. It didn’t matter who he was talking to, he would come and say to me, “Paulette.” Or he would call me over. Now, not only was he a fantastic actor, but a fantastic human being. Those are the people that I want to work with.

A massive thanks to Paulette for sharing her wealth of experience and insights with us!

Take a look at our News & Advice section for more casting stories and interviews with casting directors and agents.