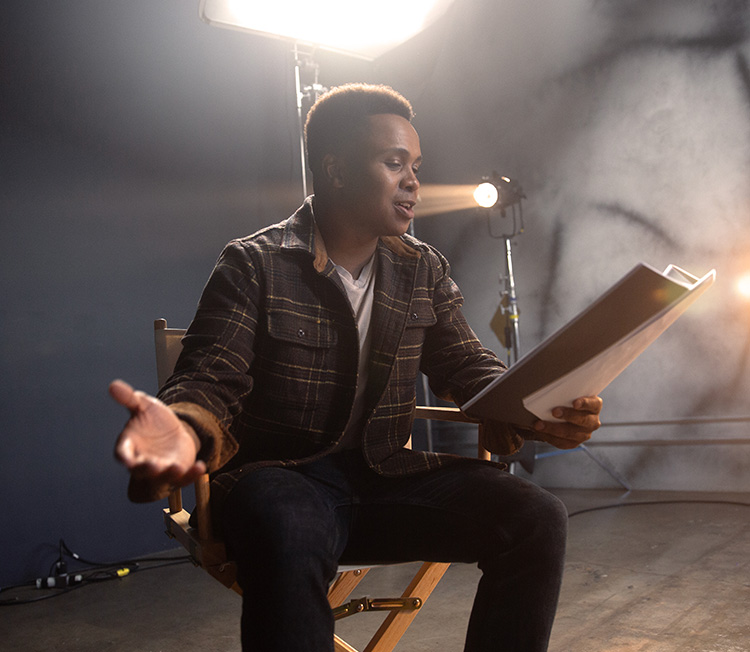

David McClelland talks about why he loves presenting, the reality of spinning lots of plates at once, and the things you need to make it in the tough presenting world – starting with his expert subject, tech.

David McClelland is a writer, presenter, broadcaster and technology expert working across television, radio, print and online. He is the resident technology consumer champion for BBC1 Rip Off Britain, a regular on ITV’s Good Morning Britain, and co-host of mobile gadget show Planet of the Apps for Challenge TV. He spoke with Spotlight about the ins and out of being a presenter, the importance of a specialist subject and how your acting training can stand you in good stead.

David McClelland is a writer, presenter, broadcaster and technology expert working across television, radio, print and online. He is the resident technology consumer champion for BBC1 Rip Off Britain, a regular on ITV’s Good Morning Britain, and co-host of mobile gadget show Planet of the Apps for Challenge TV. He spoke with Spotlight about the ins and out of being a presenter, the importance of a specialist subject and how your acting training can stand you in good stead.

Funnily enough, it was at a Spotlight event that I learned that for the 100% of preparation you’ll do you’ll only use 5% of it – but you don’t know which 5% it will be! I research intensively when I’m interviewing now. Learning how to be an instant expert in stuff, whether it’s interviewing someone or it’s the tech news stuff, is vital.

What drew you to being a tech presenter specifically, despite training as an actor?

I was born at a time when, to be an impressionable kid in the early 80s, was to be excited by technology and science fiction. It was also a time when home computers were starting to become a thing. People were just starting to welcome technology into their home. My parents went to see a film called War Games with Matthew Broderick and Kirsty Alley – they realised that this technology thing is a little bit scary but it’s certainly the future, so what can we do for our six-year-old to equip him for the future? They bought me a computer. I was very comfortable with technology from a very young age.

When it came to paying for drama school, funding for these courses was very difficult. I ended up using my technology expertise to help pay my way through it, and I was very lucky that I had Reuters – I worked with them, had a gap year and then they brought me back in my school holidays, on a decent wage. My first job out of drama school (I was still heavily in debt when I left) was to go and work for IBM. The nature of acting is contractual, but the nature of technology was also contractual. I was an IT consultant by day and an actor by night. However, by the time 2010 came around I’m married, and I’m not really satisfied with either thing that I’m doing. I went on a course at The Actors Centre, a transition course called “TV Presenting for Actors”. It was run by a lady called Kathryn Wolfe, who is a TV producer. It was two days and I remember, day one, session one, there were 8 of us and she says, “Have a specialism, because that’s the way TV is at the moment and that’s the way it’s going.”

Why is having a specialism so important for a TV presenter?

Being a general TV presenter is a very tough ask. There are some beautiful model types who will drift in, irrespective of their talents perhaps. But for the rest of us, having a specialism is your foot in that door. And I remember the penny didn’t really drop at the time, I thought, “Oh what should my specialism be? Well I quite like food!” But then someone else was an amateur chef or similar. Then I thought “Oh hang on a minute, why don’t I do this technology thing that I’ve been doing for most of my life anyway?” Everything started to click into place. You don’t have to go out and spend thousands on a presenter course with showreels at the end of it, just go out and apply for things. I went and auditioned, did screen tests for the National Film and Television School – amazing! I have got so much value out of working with the NFTS. The thing that struck me was realising I actually really loved presenting – I haven’t had any of the insecurities about performing, I’ve just been me. And if they don’t choose me then they were looking for someone else. That was when I realised that maybe I wasn’t exactly doing the wrong thing, but this was so much more me. I enjoyed saying my words, I enjoyed using my knowledge and expertise and bringing that to the panel or show. It just felt right.

What about being a journalist? Is some training in that sense helpful?

I’m not a trained journalist at all – fake it ’til you make it. Just be an expert in something. How do you be an expert in something? Well, write a book. Get yourself on TV. Have a blog, do radio – do whatever you can so that you can establish a brand. I decided to just start pitching stuff to editors. I went on some training courses about how to pitch as a journalist – I didn’t get paid for it, but I was writing for Wired at the time. Then Computer Weekly. I don’t enjoy writing at all. I enjoy the research. I enjoy the gathering of information, I enjoy pitching, I like the thrill of the hunt. But then the actual being commissioned for something, then the two or three days of pain of actually doing it… But I don’t think that I would ever just want to be a journalist – it is a means to an end to build up this brand. If I know that there are particular areas of presenting work [that I want] then I will pitch stories about that subject. That way I can go in [to a potential job] not just as David who can go on camera and read whatever and not pull a funny face, I can actually say I’ve written about this recently and these are the issues and they go, “Oh my god! You are a researcher as well as a presenter. You know this stuff.” They trust that. The depth of knowledge you get when you have to write about it, as well as the contacts, and sources [are important]. Producers and researchers come up with an idea about a thing but don’t know how to get access to that thing. And whatever I am – presenter, journalist, I have trouble defining it sometimes – I am their conduit to knowledge as well as contacts. So, my challenge is about being the conduit.

How helpful is it to have an agent as a presenter versus being an actor?

I decided that I needed a presenting agent. I did my research, pulled out half a dozen or so agents and started pitching them, because I needed an agent who would help me build those specialised relationships. It’s such a different industry to acting, short of responding to presenting work when it comes in through the Spotlight Link, there’s not a lot my agent would be able to do for me. So, I had an awkward conversation with my acting agent, telling her I would be signing up for a presenting agent. She was great about it, but she saw the writing was on the wall – I’d already had conversations about really liking presenting.

Not going to lie, sometimes it’s gotten all too much for me. It’s gradual, sometimes you don’t even notice – you keep saying yes to things, as a freelancer. You have to learn when to say no. The business aspect and mental approach to creating opportunities in presenting, the rejection and networking, it’s very similar to what you need to do as an actor.

Do you have any advice for how to actually get a presenting agent?

I emailed a bunch of them and my pitch was, to boil it down, “I will make you money.” You’re an agent, you want your cut and you need to know I’ll be working, so here’s the work I’ll be doing. I pitched to agents that had a mixture of talent on their books – maybe one other big name in terms of technology – because I knew that they would have lots of inquiries. My agent had Philippa Forrester and Susie Perry from the Gadget Show, for instance. They will get a lot of phone calls from companies wanting to book Susie Perry, if she’s not available because she’s filming, who else are they going to recommend? That was almost exactly 6 years ago.

How did you find the process of starting to get work as a presenter? Any top tips for others starting out?

[After getting an agent] absolutely nothing happened for 8 months. [Then] I got a call from a researcher at the BBC saying, “We are looking for someone who can take apart an iPhone for a pilot for a TV show. Have you done that before?” I was like, “Yes, of course!” I hadn’t – for the next three days, I ordered all the parts, I took apart an old iPhone several times, I rehearsed everything backwards and forwards. This is where the preparation as an actor came in I guess. Knowing how to hit the mark, the level of preparation needed to just turn up and deliver something.

They didn’t pay me for that – I said no to it originally because I wanted to see if [the BBC would] offer me some money. They didn’t. I’ve decided it has to meet my ‘Rule of Three’ – it’s a rule that I go by as to whether I accept the job or not. So, the first question is: Is it good for my cash flow? Is it good for my CV? Is it good for my soul? It needs to tick two out of three. Sometimes you get a feeling about it, and if it only ticks one, you have to question why you are doing it. The impact that that one job had on my career- suddenly it was David McClelland, BBC. All of a sudden, corporate jobs started to come along. I had a meeting with my agent who said to me, “Not going to lie, the broadcast stuff is great, but the corporate stuff will be your bread and butter as a presenter.” At that time, I was far too idealistic, but actually that was a game changer. I started getting offers of work without a casting, a screen test – lots of stuff that would never happen in theatre, just being offered jobs on the basis of being on the BBC, knowing technology, etc.

Funnily enough, it was at a Spotlight event that I learned that for the 100% of preparation you’ll do you’ll only use 5% of it – but you don’t know which 5% it will be! I research intensively when I’m interviewing now. Learning how to be an instant expert in stuff, whether it’s interviewing someone or it’s the tech news stuff, is vital. I’ll get a call at 10 o’clock at night that these hover boards are exploding or something, and asked, “Can you come in for tomorrow morning’s show and talk about it?” The answer is “Yes, absolutely, I know everything about this subject!” You just have to go with it, and fake it ’til you make it.

What’s the work-life balance as a freelancer? Are there things people should know about working in this kind of role?

It is really exhausting and I think if you also have a day job, you’re trying to balance the flexibility of that. I live in London, I’ve got a 4-year-old and a 7-year-old. That isn’t cheap. It means working late nights. I think back to 2012 when things were just starting to take off, there weren’t any weekends – I was really busy, whether it was researching stuff, putting together my website, putting together showreels, actually doing jobs and being away from home. I do enjoy the travel, I like variety. It became obvious though that being away for 12 weeks at a time wasn’t practical for us and our family, our happiness. But actually, being away for a week at a time worked. I’m fortunate in that my wife is incredibly supportive.

Not going to lie, sometimes it’s gotten all too much for me. It’s gradual, sometimes you don’t even notice – you keep saying yes to things, as a freelancer. You have to learn when to say no. The business aspect and mental approach to creating opportunities in presenting, the rejection and networking, it’s very similar to what you need to do as an actor. I just find the TV world much more natural, though I still do panto every year.

Where do you think the future of tech presenting is going, specifically?

It’s interesting you said ‘specifically’ at the end of your question – I think that’s it. When I was first interested, knowing about tech was kind of enough. But nowadays there is so much tech, I think it has to be more specific. I turned 40 last year, and I’m not going to be getting excited about phones and tablets and smart watches in the same way. I think it’s much more of a young person’s market. I think maybe cybercrime, and similar – the things I focus on tend to be human interest, not just, “Cool, it’s tech!” it’s more about how this will affect your life? The challenge that we have is how do we do anything with tech on television, without it being someone sat on a laptop? There have to be creative ways of presenting tech. Finding creative ways to make tech work on television is essential for when you are pitching to broadcasters, for them to take you seriously.

Any final advice for potential presenters?

I would echo the advice I was given right at the beginning of this: have an expertise, and make sure it’s something you’re passionate about. You will spend time away from your family, late nights, in order to be able to hit the mark and deliver above and beyond. You’re going to need to do so much work, so if the subject’s not something you’re passionate about, you won’t stick with it for very long and it will be so much harder than it needs to be. Having a grounding in some of the on-camera techniques is good, but just remember that you have to be able to talk about the thing – be interested in it, that is enough. Having that thing – that story to tell – is really important.

Thanks very much to David for taking the time to chat to Spotlight! See what David’s up to on Twitter or via his website.

Images courtesy of David McClelland