How to begin writing, develop a monologue and what to bear in mind when turning that monologue into a full show.

When it comes to writing – in all its forms – starting can be the hardest part. We want to make sure whatever we write is perfect, but the first words rarely are. Writing, like almost everything worth doing, requires practice and if you never let yourself write badly, then you’ll never get good.

So, how can we encourage ourselves to write without self-judgement? And how can we then turn those scraps into a monologue worthy of performance?

Improving With Freewriting

It’s easy to imagine ‘genius’ writers as people who get struck by lightning and then spew out Romeo and Juliet. Maybe this is the case for one in a million, but for the rest of us, it’s a slog. If you learn to play the guitar, you’re not going to sound like Jimi Hendrix when you start out. You’re unlikely to be in tune, let alone a good player, for the first year of playing any instrument, and yet we expect great writing to happen immediately. Writers have their ugly duckling phase, too.

One way to improve fast is by freewriting:

- Set a timer for 10 minutes.

- Put your fingers on your keyboard or pick up a pen and start writing whatever comes to your mind.

- Don’t slow down, hesitate or censor yourself. Try to get lost in your head and go for a wander in your imagination.

- Write continuously until your timer goes off.

To get noticeably better at writing, you could do this every day. It will cure you of your fear of the blank page.

Dealing With Writer’s Block

Writer’s block is simply constipation of the imagination. How do you overcome constipation? Fluids. So, write more fluidly – freewriting is one way to achieve this. By writing quickly, often and without pressure or judgement, we outrun ourselves, tapping the stream of consciousness.

Another cure for constipation: change your diet. In this case, your ‘cultural diet’ – theatre, films, TV, books, music, art, etc. If you’re feeling stuck, try to engage with stuff you’d normally avoid. Inspiration can strike anywhere, often coming from the most surprising places.

Editing Freewriting into a Monologue

Once some weeks or months have passed and you have pages and pages of your freewriting endeavours, it’s time to go hunting for diamonds. Just as real diamonds are found in the dirt, you will have sentences or paragraphs among the not-so-good parts of your writing that are truthful, funny, wise, haunting or which communicate to you something tangible.

Read through your writing, highlight the diamonds you find, cut those parts out and put them together in another document. If you did this for, say, two months, you’d have a document of good fragments culled from the dregs of your terrible writing. Perhaps you could make a monologue by stitching together the best of these lines? Maybe, with a little rewriting, these fragments could add up to a meaningful whole?

“How do I know what’s good and what’s bad?” I hear you scream. Well, when editing your work you must first use your own tastebuds to decide what’s a diamond and what’s dirt. When creating any work of art, you need to first please yourself. If you like what you’ve created, there’s a chance I might like it, too – and if we both like it, there’s a chance some others will. But if you don’t like it, then it’s unlikely I’m going to be impressed by it, and even if I was, that would feel like a hollow victory to you.

You are your own best judge – please yourself and hope the world agrees.

For those writing comedy, if you’re writing something funny and not laughing at it while writing, then it isn’t funny. Likewise, you’re writing drama or tragedy – if you’re writing something emotional and not feeling strong emotions while writing, it isn’t going to captivate or haunt an audience.

You are the audience! Never forget it.

Writing Your Monologue

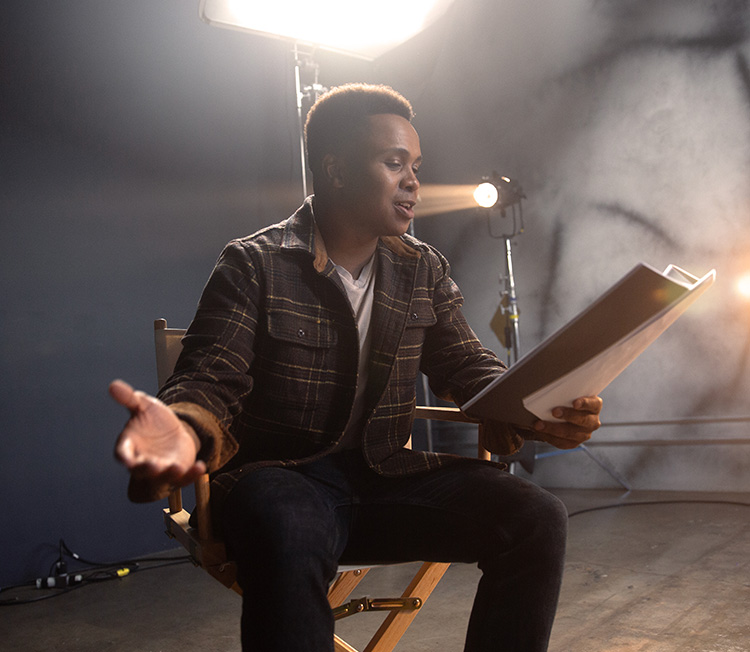

Monologues are one of the most common ways that we measure actors by. You have to do an audition monologue to get into a play, film or drama school. However, we shouldn’t think of monologues as a necessary evil to get work. They’re the purest form of acting – one where you’re completely self-reliant. It’s just you and the audience; sink or swim.

Monologue means ‘one voice speaking’. There are infinite forms that might take, but here’s a few off the top of my head:

- Storytelling

- Stand-up comedy

- Character monologue

- Poetry reading

- TED talks and lectures

- News reports

- Court testimonials

- Witness and suspect statements

- Political, wedding or acceptance speeches

- Eulogies

- Voice notes and answering machine messages

- Sales pitches

- Sports commentary

- Religious sermons

- Rap battles

- Shakespearean sonnets and soliloquies

- Verbal diarrhoea

Some of the above are performance modes or styles of theatre; others are monologues we might encounter in real life.

As a writing exercise, pick one from the above and write it, letting the words guide you. If you get into flow with the words, they may reveal who is speaking – you, or a stage persona version of you, another person from real life, or a character you might portray?

Or, maybe you’d like to start by designing the character. Here are a few provocations:

- What’s your Type Casting? Why not go against the grain and write yourself a role that nobody else will write for you? Have you got a dream role that is against your usual type? Now is your chance!

- If you decide to go with the grain and write a character who is your usual type casting, don’t go for cliches. Subvert the expectations that the audience might have, deepening the archetype you are trapped in.

- You probably aren’t going to write a monologue for a character who already exists, like ‘Juliet’ from Romeo and Juliet. But if you’ve previously played a role to great acclaim and deep satisfaction, you could think about what you liked about being that character. Which aspects of Juliet did you relish bringing to life? Create a new character that embodies these qualities, perhaps cross-pollinated with characteristics not found in the original. Try not to plagiarise – life is hard enough without Shakespeare’s ghost haunting you!

How to Make a Show Out of a Monologue

If you plan to turn your little scrap of a monologue into a full show, there are certain decisions you’ll need to make and things to keep in mind while writing your monologue:

- Are you going to acknowledge the audience or not know that they’re there? Is this ‘rule’ consistent across the show or does it depend on which scene you’re in? If the audience is acknowledged, are they addressed as an audience? Or as though they are a particular character within the narrative? If those feel too restrictive, it might still be useful to have an attitude towards them. A good rule for storytelling – tell it as though to a good friend.

- Is your show one story all the way through from beginning to end, or many little stories? Be warned: if you’re aiming for an hour long show, you need more content than you realise. If you’re aiming to tell just one narrative, it needs to be a doozie. How many yarns take an hour to tell and can hold the listener’s focus the whole way through?

- Monologue means ‘one voice’, but are you one character or many characters? If you’re a chameleon actor, playing different characters is a good way to show off the different acting you can do. But you need to find a story, concept or theme that unifies those elements and justifies them.

- Uniqueness is perhaps the most vital component of any artist’s work. Without it, you are redundant. As a performer, ask yourself what you can do that no one else can. In a monologue this is doubly true: how can you make people glad it was only you on stage instead of wishing other actors were up there with you?

- Weave the unlikely together – this is a good idea no matter what art you make. Look for elements that don’t look like they’ll go together and force them together. Uniting opposites is a principle of design, and in a work of art or entertainment, adds depth and dimension.

- Live theatre is a time-based medium, and every artwork is a hunt for meaning. Your job is to think of your show as a series of questions posed to the viewer. You want them to be asking what will happen next, you want them to be thinking, ‘Tell me more.’ If you can be specific and meticulous in the questions you’re attempting to pose and playful in the posing of them, there’s a chance the audience will pick up what you’re transmitting and enjoy it, too. If you don’t attempt to communicate anything meaningful, it’s very unlikely that you will.

- Aristotle is an ancient dude that knew a thing or two and he said (paraphrasing now, but this was the gist): “The ending is difficult because it must be both surprising and inevitable.” So be wary of the ending that is too obvious. If we get to the end and it’s exactly what the audience assumed it would be (I’m looking at you, romcoms) then the artwork comes off as redundant – we didn’t need to watch it. But, be equally wary of the opposite kind of ending, one that is totally random and could never be guessed from the outset. The sweet spot is an ending that we could have seen coming at the outset of the story but we didn’t. You may need to try many endings before you find the one that works.

- Finally, a word from thriller writer Elmore Leonard: “Once the story is over, get the hell out of there.” Bad writing hides at the end of the tale, once the story is over, but the author refuses to shut up.

With that in mind, I’m out of here! Thanks for reading!

Take a look at our website for more writing advice and tips for performing your best monologue.