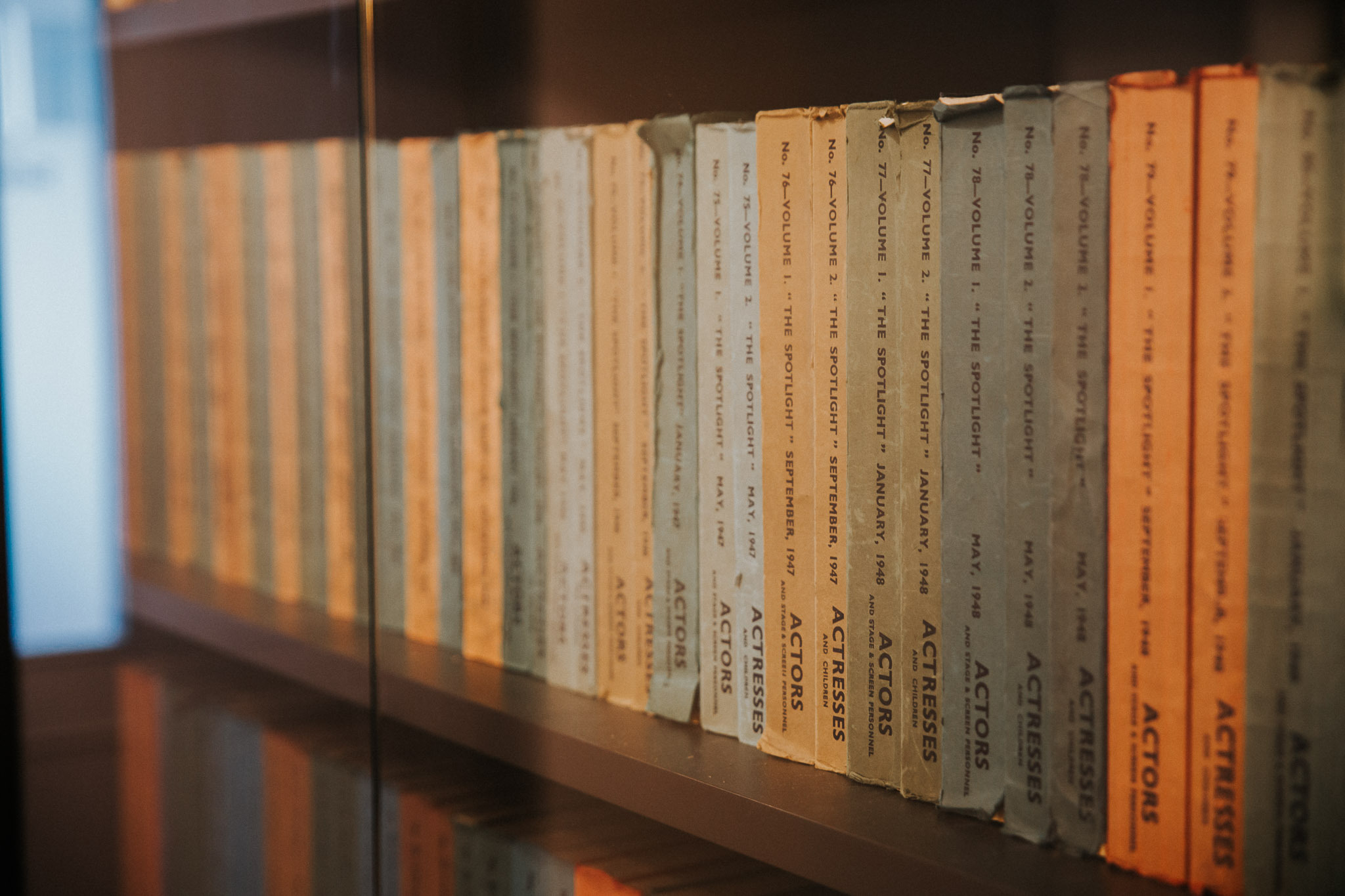

Spotlight spoke with Amber Onat Gregory, co-artistic director of Frozen Light, who specialise in creating multi-sensory theatre for audiences with Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD). Amber shares her inspiration for creating the company, how they develop their work, and how she balances running a theatre company with parenthood.

Lucy Garland and I studied theatre together at the University of Kent in Canterbury. [In] our final year you could specialise in a specific area, and we specialised in applied performance, which was a Masters year and looking at applying performance to community groups.

One of our placements that we did together [was] working in a secondary special needs school in Canterbury St. Nicholas’ School. And it was interesting because up until that point the applied theatre world we were exploring was issue-based theatre [but] the class we happened to be put into was a class of six teenagers with PMLD.

So, then myself and Lucy, we graduated in 2007, we went our separate ways. And then we both did other work: Lucy did a lot of work in street theatre, I did a lot more work in prisons and detention centres. We did different things, but both continued to perform and create small scale multi-sensory theatre in special schools, and then after being freelance artists for eight years, we both reached a point in our career where we just wanted to do something bigger. We saw a massive lack of provision for audiences with PMLD in theatre venues and realised we had the skills and desire to fill that gap.

Lucy, at that time, was also working as a carer in an adult day centre, I was doing a lot of work in London special schools as a teaching assistant, so we were both seeing people’s lives from within the system as well, and just seeing the huge lack of provision outside of schools.

We made the commitment to then brand ourselves as Frozen Light, with the commitment of touring high-quality, sensory theatre only to theatre venues.

The Isle of Brimsker is our fourth production, and all our shows are original devised pieces. We have worked with a musician, Al Watts, from our very first show, and Al has always been in day one rehearsals with us. Live music has been a hugely important part of our work. As our work developed, we realised the need to have the set designer in from the first day as well, and that’s because, when we create work, instead of starting with the story, we flip theatre-making on its head and we start with the environment.

With The Isle of Brimsker, the original concept was to see how we could visualise sound in a way other than hearing it. We worked with Al and Katharine [Heath, a set designer] for two weeks, initially developing the show, and that was just playing with sensory props and playing with sounds and music, and the sound waves eventually brought us on to actual waves, that then brought us onto an island, and then the concept moved from visualising sound to where the sea meets the rock.

We were the first company to take work specifically for audiences with PMLD to the Edinburgh Fringe. That was really exciting for us, particularly because, since we started the company, everyone’s [told us] you’re not going to be able to tour Edinburgh, because Edinburgh’s not accessible. And then we started thinking why? There must be wheelchair users in Edinburgh! I think it was just an excuse that the industry had for Edinburgh not being accessible, and that became an excuse we had for why we didn’t go there.

So, we said, no, we need to get to the Fringe. And it was interesting because we were so worried about it, we were so stressed about it, and then we got there and it was just so easy. It was possibly one of the easiest touring experiences we’ve ever had. We toured at the Pleasance, and all of the Pleasance’s venues were wheelchair accessible, so that felt like a really amazing fit. The Pleasance was so understanding that we needed longer get in and get out [time].

I really enjoyed the work that I did particularly in prisons, and I did a lot of work with detention centres and asylum seekers and refugees, but all the work I did in that area, I did alone. Not only is that a difficult environment to work in alone, but actually when myself and Lucy started working together, I really saw how great collaborating with another person can be.

One of the best things about being an actor working with this audience is the fact that responses are so varied. We had a moment where the character cries during the show, and we’ve had times where the audience has come up and hugged the performer onstage, which is really lovely. We’ve had some shows [where] we have quite a few audiences with autism, who wander around quite freely.

But all of that makes the work a lot more interesting, and it makes it a much more diverse experience for the performer. It makes you a very strong performer, you can’t be precious. That’s when you realise that doing a theatre show is not about you, it’s about your relationship with the audience, and I think in a lot of theatre it can be very easy to forget that. But our audience don’t let us forget that. We’re constantly reminded that this show is for them.

As an artist, I can sit there and say, “Oh, you want to create work for audiences with PMLD? That needs to be for an audience of 6,” or “It has to be multi-sensory,” or “You have to do it at close proximity.” That may be true for the work that we’ve created, but I’m not going to sit there and say that is true for all art, and all theatre for our audience. I’m very, very open for artists to come along and try out new ways of making art and theatre that’s accessible for this audience.

I’m really interested, as a theatre-maker, to be saying to an emerging artist, what do you want from me? Is it that you want to learn how we make theatre accessible for audiences with PMLD? That’s fine, we can talk about that. But also, do you also need to be learning about how to talk to venue programmers about programming work that makes a financial loss, because it’s for such a small audience? Do you need to learn about how to be looking for venues that are accessible for wheelchair users?

As an artist, I just want to make the art I want to make, so I don’t want to say to another artist [that] you need to make your art in this way, because they might have another idea.

One of the things I’ve definitely found hardest about being a parent and running a theatre company are people’s perceptions of what you should do when you have a child. So, for example, I never really wanted to take maternity leave. It wasn’t something that was important to me – I really wanted to just be able to keep working whilst having a child.

When they were really, really little, in some ways it was actually a lot easier than now, because they just came on the road with me. The difficulty I had was when my eldest started school, which was 2 years ago, and as soon as he started school, all of a sudden it was like, well, you can’t come with me. At the time that he started school I’d just had another baby, so my mum came with me on the road, and arranging the child care back at home, so that he could still go to school, was extremely challenging.

I made the decision after that development that I would do the first part of this The Isle of Brimsker tour, which was 10 weeks long [and then] I would take a step back from touring. When I made that decision, it felt very attached to motherhood, and I felt quite sad about [leaving the tour]. But at the same time, it’s given me the opportunity to see what else the company can do.

I would say theatre is what you want it to be. As a performer I never went down that agent route. You can make theatre what you want it to be, so just to remember that theatre is very broad, and the industry is very big, and there’s lots and lots of different ways of doing it.

Thank you Amber for that insight. You can learn more about The Isle of Brimsker’s tour dates and venues by clicking here!

Image Credit: JMA Photography