From his Olivier Award-winning role in ‘Wolf Hall’ to working with Ridley Scott, Nathaniel Parker shares his career highlights and details about his new play, ‘Ragdoll’.

Nathaniel Parker is an actor with a career spanning over four decades, instantly recognisable to millions as ‘Inspector Lynley’ from the long-running BBC series The Inspector Lynley Mysteries. His performance as ‘Henry VIII’ in the award-winning stage production of Wolf Hall earned him an Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and he’s since graced the screens in productions like Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel, Midsomer Murders and The Doll Factory.

As well as being a talented actor, Nathaniel has also served as an executive producer on the acclaimed series The Beast Must Die, and shares his love of poetry through his Instagram account by doing regular readings.

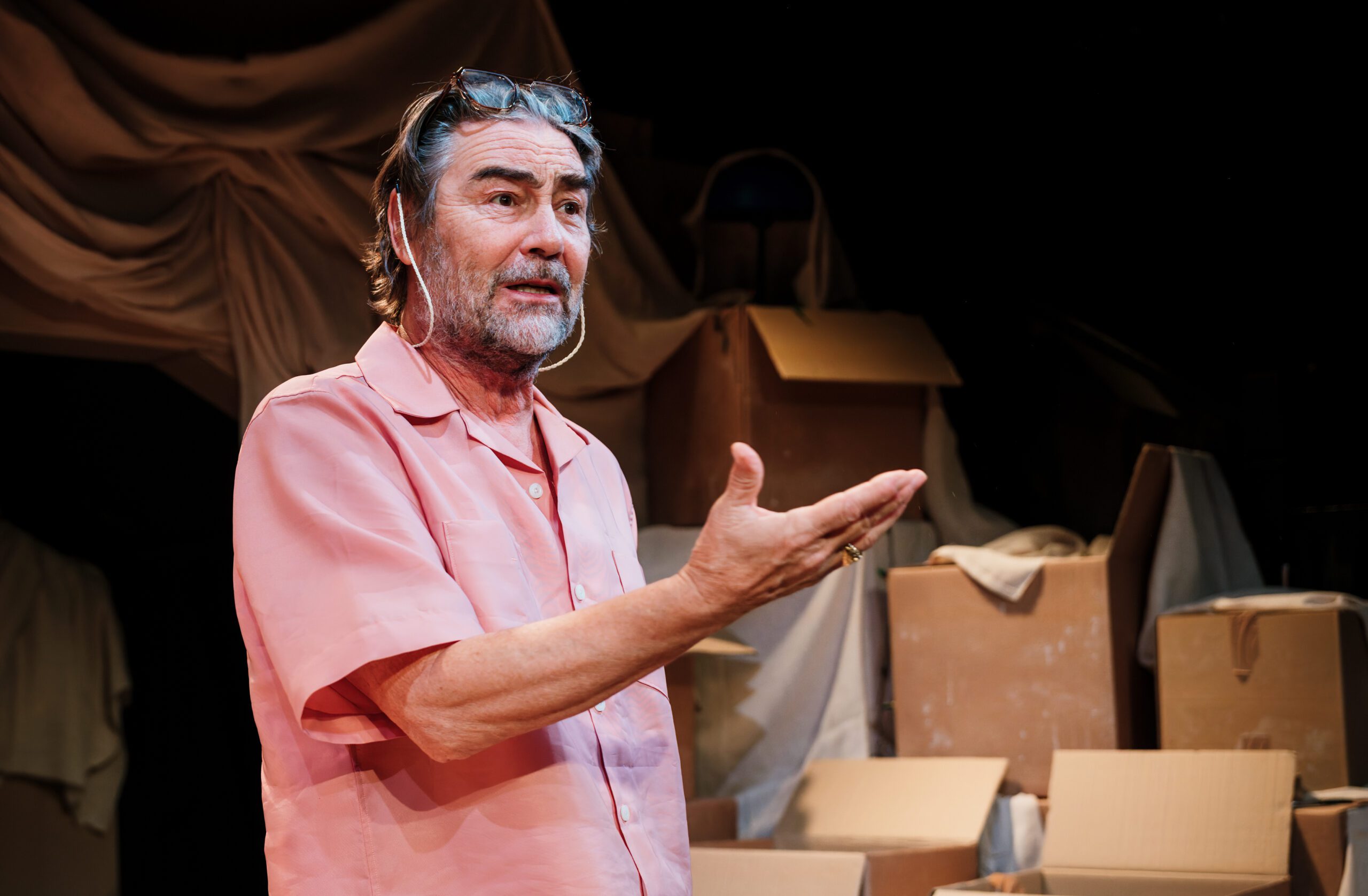

Most recently, Nathaniel will be performing in Ragdoll, Katherine Moar’s new play, at the Jermyn Street Theatre. Drawn into this project by gripping dialogue, the challenge of playing a character that’s very different from himself, and the joy of being the first to play the role of ‘Robert’, Nathaniel has nothing but praise for the experience of working with both Katherine and the play’s director, Josh Seymour.

With the show now having begun its limited run, we caught up with Nathaniel to discuss his extraordinary acting journey. From struggling with undiagnosed dyslexia and playing ‘Inspector Lynley’, to his latest artistic endeavour at Wilton’s Music Hall and how he became involved in Ragdoll, here’s what he shared:

In this interview, you’ll find:

- An account of Nathaniel’s childhood realisation that acting was his destined career path.

- A look back at Nathaniel’s major career highlights, including his long-running role in The Inspector Lynley Mysteries and the significance of playing ‘Henry VIII’ in Wolf Hall.

- Details on Nathaniel’s expansion into executive producing for television and his current collaborative role in the new play Ragdoll.

- Information about Nathaniel’s personal artistic ventures, such as performing T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, and the most impactful acting advice he has received.

Hi, Nathaniel! What made you first want to become an actor?

I love that question because nothing made me want to become an actor. I wasn’t going to do anything else. I realised when I was nine. Up to that point, I’d wanted to be a train driver, an astronaut, Fred Astaire, a cowboy, Tarzan – anything I’d seen on telly. I wanted to be all those things and lived through every moment of every programme or film that I watched. I remember watching [Laurence] Olivier when I was five, and I was just thinking, “I want to be Henry V. I want to be everything.”

When I was nine, I took a train by myself from London to Cambridge to see my sister in her first term at Cambridge playing Lady Macbeth. And when she came on, I just went, “I see, I can be a 12th century Scottish king or a doctor like my mum without six years of practise. I can just do three weeks of rehearsal. This is fantastic. I could just be an actor.” So it became a realisation rather than a choice.

I’ve wanted to do other things along the way. I wanted to, at one point, emulate my mum and be a doctor, but I’m dyslexic, and that doesn’t help with exams. I had a brother who’s now a film director – Ollie [Oliver Parker], who could do crosswords in Latin when he was 11, another brother who did his A-levels at 16, and a sister who I think has got four different MAs from around the world. I was not an intellectual or an academic like they were.

For a long time, I thought myself a bit dim. But when I was 42, I discovered I was dyslexic, and that made a lot of sense. You’d think, wouldn’t you, that dyslexia makes it harder sometimes to learn lines, but I know a lot of people in the arts that are dyslexic. It’s not a novelty anymore, and neither is my ADHD. Everybody’s on the train now. But I adore it. I think none of the characters I’ve ever played have been dyslexic, which I think helps me learn my lines. I don’t know. I must be fooling myself on that one, but it’s true. And I played a lot of lecturers and professors recently over the last five or six years. And so they’re as smart as anything. And I guess I realised at 42 that, yeah, I’m not that dim, I just don’t see words in the same way that others do.

I remember my dad putting me to bed one night and saying, “Do you see the swirls on that wallpaper? What does that look like to you?” And I went, “Oh, well that’s a cloud and that’s an elephant.” And that’s when he said, “Yeah, that’s called using your imagination.” And I’ll never forget that. So I think without that, I would’ve been sunk.

How did you get started as an actor?

I didn’t want to go to drama school. I wanted to go to university. I was at a school called Leighton Park just outside Reading – a Quaker school. It was a boarding school, and I’d slip out after my prep and go and join a local amateur dramatics theatre company. I don’t think the school knew, but I was in plays in Reading while I was at school. I found myself then thinking, ‘Okay, I can just go straight into it. I’ll just go straight into it.’

There was an actress I’d met who was fantastic, I thought. She went to Hull University, so I thought, ‘That’s what I’ll do. I’ll go to Hull’. So, on my UCCA forms I put on my five top universities to go for: Hull at the top, then Bristol, Manchester, Oxford and Cambridge. Funnily enough, none of the others replied, but Hull did.

I’d just done a play, Sergeant Musgrave’s Dance, and I played ‘Musgrave’. I went into my chat and this professor showed me the theatre and they were doing Sergeant Musgrave’s Dance. I started quoting it and he was obviously really impressed because by the time we got back to his office, he said, “So, what would you like us to offer you?” And I went, “A couple of Cs and a D will do me, thank you very much.” But I didn’t get anywhere near it, so I didn’t get into university and I thought, ‘What am I going to do?’ I retook A-levels. And then I thought, ‘Well, I suppose I better go to drama school and learn’.

I was at the National Youth Theatre. I had a great time there. People like Douglas Hodge, Sally Dexter, Colin Firth and I became really good mates at that place. It was really fun. It was a whole new experience. And people like Colin were getting into Drama Centre and a lot of people were going to various drama schools, so I thought I better try.

I got into LAMDA and, honestly, it wasn’t my favourite place in the world. I found it quite cliquey and difficult. The actors who’ve come out of it, when I meet them again or see them, I just have nothing but admiration for them. How they stuck at it as well, I don’t know. We had really good actors, but it felt difficult for me. I was never part of a group.

I was very lucky. In those days, you needed an Equity card. Somebody was inevitably offered that, and different jobs and agents came to them. I’d happened to play a really good part – ‘Captain Brazen’ in Trumpets and Drums, which is Brecht’s version of The Recruiting Officer. I had such fun playing him and I was luckily offered lots of different things and lots of different agents, and I felt quite secure for the first time. I’m still picking up things sometimes that I learned and going, “Oh yeah, I remember then they had that class. I did this, didn’t I?” Still now, 40 years later.

How did you first get involved in ‘Ragdoll’?

Initially, you’d think it was a radio play for me because I am meant to be late 70s and an LA lawyer originally from Boston, but he’s lost that. I’ve just done [The Twelve Dates ‘Til Christmas] for Hallmark, where I had the amazing Mary McDonnell as my ex-wife and Jane Seymour as my girlfriend, and I got a phone call that said, “Here, sending a play. Have a look. See what you think.” Over the last few years, I’ve been very lucky. I’ve done a lot of theatre over the last few years – had an absolute ball. I mean, I’m astounded how poorly paid this business is, but the parts are great.

I’ve done some new plays and I’ve worked with some fantastic writers over the last few years. Hilary Mantel when I was doing the Wolf Hall series, and Tom Stoppard. So I’m quite used to working with writers at the moment, and I thought, ‘Okay, let’s see what this one’s like’. Katherine Moar, she wrote a play called Farm Hall, which was on at the Jermyn Street Theatre when I was at Southwark playing the same story by a play written by somebody else. So it was quite interesting. I thought, ‘I’ll read this and see what I think’.

And like those other really good playwrights, I found myself reading the part out loud as I was reading the script, which is an indication for me of proper talent, and I’m identifying with it straight away. [‘Robert’ is] very different from me and I think this is going to be a fun challenge. This is going to be something different. And the joy, of course, of playing in a new play is that you are forging the road. Nobody else has done that one and nobody else has played this character.

When I played ‘Henry VIII’ in the Wolf Hall series, lots of people have played Henry VIII, but nobody played that one. A lot of people have done A Man for All Seasons or Shakespeare’s Henry V, but no one had played Hilary Mantel’s version of Cromwell’s version of Henry VIII. And no one has played Katherine Moar’s version of Robert before, who is loosely based on a real character. And I just thought, this is going to be so exciting.

The dialogue zips through, it’s fantastically clever, really inventive stuff, challenging. People often use the word rollercoaster, but it’s cleverer than just going up and down. It’s going round and inverting itself and going back again. And we’ve got Katherine in the room. So I read it and I thought, ‘Okay, this is going to be interesting’. So I had a long chat with Josh [Seymour, the director]. I went to see Josh in a cafe in town and we talked about it, and I came away thinking, ‘Yeah, this is really getting more interesting by the second’.

You know, when someone’s offering you a part, inevitably they flatter you a little bit, and I’m a sucker for that, frankly. Flattery will get you everywhere in my book. So I spoke to Katherine, and actually, she didn’t really flatter me that much. It was more about what she saw Robert to be and how different he was from the other. There’s two characters in the play, Robert and Holly, and they’re in 2017, at the beginning of the Me Too movement. Then there’s two other actors in the play who are playing the same people but young, back in 1978. It’s very clever.

Image credit: Alex Brenner / Nathaniel Parker as ‘Robert’ and Abigail Cruttenden as ‘Holly’ in ‘Ragdoll’

She then started comparing me to the younger one, saying, “He’s got to have changed like this and he needs to have developed, and what we’re seeing now is this.” And that’s really great. It’s a very exciting thing to do. So you’re partly basing it on a real person, which is always a fun challenge, but also having the imagination to take it beyond that and do your own interpretation of somebody.

The writer isn’t always right just because the word sounds the same – writer and right. They can be challenged, and Katherine is very accepting of that challenge. She’s almost always right, it has to be said, but there’s a really important talent, not just as a writer, but as a director and as an actor, too. It’s not often used enough as a producer, but I think it’s a really good talent for that too.

I remember being told this by my brother twice in my life, once when I was about to play ‘Macbeth’ for the National Youth Theatre, and the other time I was about to direct. And he said the same thing: “Just listen to what the person has to say.” If someone comes up to you, if you’re an actor, listen to what the other character says. And if it’s good writing, you’ll know how to respond. And if you’re directing or on the other side of the thing, then listen to whatever he says because if you interrupt somebody, then they haven’t finished telling you their idea, and their idea might be the thing that unlocks everything. So, let them have their idea, and if you don’t use it, fine – they won’t resent you because they’ve been heard.

It’s a really good tactic. I’ve been on film sets with Ollie many times and I’ve seen him do that, and the sets have always been wonderful sets. People have really enjoyed the process because he listens. Katherine does that, as does Josh. They really do listen and they let me say what I have to say. And sure enough, they often don’t use it. It’s really great to have been heard, and look, I’m enjoying the process.

How do you choose which projects and roles to take on?

I did a play at Southwark a few years ago, which I didn’t have much to say in. I hadn’t done any theatre for a while. From there, I thought, ‘I really need more words’. And then I did Rock ‘n’ Roll with Tom Stoppard, which was full of words. It’s the moment you identify with somebody and somebody thinks you identify with them, so you give them a shot and go, “Okay, let’s see if I do.” And there are some things which I don’t identify with. I often see actors go, “Why were you asked? Why did you choose to do this?” And more often than not, the question is answered by, “I was offered it. I had nothing else to do. They’re paying me, I’m doing it.”

I have been very lucky recently, and I have read some plays and a lot of them have been fantastic, but the ones that really, really gripped me are the ones I’m able to do. There’s a lot of experience there now. I’ve been around the block a couple times, but the greatest thing is you do some of this and you’re learning again. I just love that sensation.

I did a Hallmark series earlier this year for Christmas – The Twelve Dates ‘Til Christmas. I’d never done anything like that. Working with Jane Seymour, Mary McDonnell and Mae Whitman, who was playing the lead. That was an experience. I’ve done TV shows before, I’ve done series before, but it was completely new to me to do that, and every day was a joy.

You’ve recently been reading poetry on your Instagram account. What made you decide to do this?

I started doing it because poetry has always been a huge part of my life, without sounding pretentious. My dad was, I think, at one point, chair of the William Blake society. It was integral to his life, William Blake, and I remember him teaching me and Ollie about Blake and getting us to learn poems as kids. Like I said, I was dyslexic. He used to have to pay me. So I was paid a sixpence to learn ‘Tiger Tiger, burning bright’. I found the financial incentive really worked for me.

I have a voice that can sometimes resonate with poetry. Although I remember when I was at my Quaker school, you’d have ‘Collects’ instead of an assembly or meetings sometimes, and you were able to stand up and say something if you felt the need. And I would rather pretentiously stand up and recite poems.

I remember reciting Once the Lamb by William Blake, and afterwards, my English teacher came up to me and said, “I had no idea it was so sinister.” I go, “Oh shit, got that wrong.” So I’ve got to be careful how I sound. My oldest brother actually suggested it to me, Al. And so I thought, ‘Yeah, I’ll do it’. And a year and a half ago, I just started reading poetry on Instagram and I went through all of Songs of Innocence and of Experience, which is where I feel safest, with Blake. Then, I started going off a bit on different jams – I’ve read the whole of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, I’ve done [poems by] various amazing women.

I’ve never done this before and I feel kind of nervous about it. I’ve booked myself into [Wilton’s Music Hall] to read some poetry. About four or five years ago, I read T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land at Cheltenham Literary Festival, and I fell in love with it as a poem. I think it’s extraordinary. The lady who runs Wilton’s, Holly [Kendrick], said, “We’d love to have you there.” I said, “Really? What? Reading poetry?” She said, “Yeah, why not?” So I put myself in on the 15th and 16th of December. And it’s selling really well! I think they’ve sold 85% so far.

I’m starting with reading The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Then I’m having a chat on stage with Giles Taylor, who’s a wonderful actor that was in all the Wolf Hall trilogies with me and other plays. I’ve known Giles for a while and I trust him enormously. We’re going to have a discussion about The Waste Land and all the incredible imagery that’s in it and the references. Hopefully I’ll give the audience a bit of a mental bingo card that they can check off as we go through them. There’s a bit of German, Italian, French. So I’ll give them the translations first and then I’ll do the poem. It’s only an hour or so long.

I’m really looking forward to it. It’s just kind of weird because I’m employed to do things, and this is me employing me to do things. If it goes well, who knows? Maybe I’ll do it more and take it around the country a bit.

What are your career highlights and why?

One of them was the first short film I shot with my brother directing, which my wife was also in. It was shot at our house. We did all the costumes, make-up, food. I was being the devil as a painting. And the first time he said action, I just looked at him and sobbed and thought, ‘That’s such a wonderful, proud moment. My brother’s finally found his feet from being an actor and a writer to being a director’. So that was a really proud moment.

Being ‘Henry VIII’ [in Wolf Hall]on Broadway, being in London and Stratford – just fabulous to be working with that. I wasn’t on stage to receive the Olivier, but that’s probably one of the proudest achievements I’ve ever had.

Being in a Ridley Scott film, The Last Duel, was amazing. Sitting with Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, Jodie Comer and Adam Driver. Amazing experience.

Or producing. I produced a TV series called The Beast Must Die, which had my mate, Jared Harris, Cush Jumbo, Billy Howle and myself. Turning up on set the first day as a producer on that was oh my god. So, yeah – lots of proud moments, I’m afraid! I live in a place of joy most of the time.

Image credit: Charlie Carter

What was your producing experience like?

Up to that point, I’d only produced a couple of short films. My daughter did a short film, and I was in it and producing it, and you’re literally washing pans at two in the morning, up again at six, making breakfast for 30 people. It was relentless and exhausting.

Doing [The Beast Must Die] with Scott Free Productions on one side and New Regency on the other – amazing producers to work with – and little me in the middle. You only have the odd lunch, deciding on takes and, “Let’s have a look at the script and do…” Absolutely brilliant feeling. And having an input from the word go like that. I absolutely loved it and I’d love to do more.

Getting something off the ground is so difficult. I had this image that once I’m a producer, everyone will come and see me. No, it’s not like that. You produce your own stuff and it’s really hard. It’s a really hard, slow process. But I’ve got a couple of things up my sleeve, so I’m hopeful.

Do you think your acting experience helped you with producing and vice versa?

Definitely. It’s dangerous to bring the producing into acting because it can distract you. There’s a couple of plays I wanted to do once, and I got really well-advised by proper theatre producers who said, “Don’t do it. Don’t produce and act because your mind isn’t there.”

But on TV or film, it’s very different, and it definitely helps. If you’re an exec producer, like I’ve been, you’re looking at a perspective that most of the other producers haven’t got. And it is really helpful. A lot of the best directors I’ve ever worked with have been actors because they’ve really understood it. Not all of them – Ridley Scott was never an actor, and he’s not bad, is he? But people like Jeremy Herrin. Ollie, my brother, understands what it’s like to stand on the stage, and I think that’s really helpful.

You’re probably best known for your role of ‘Inspector Lynley’. Looking back, what did this role teach you about acting?

[The Inspector Lynley Mysteries] started in the 2000s and I’d already done quite a lot – period dramas and films and stuff. But what was great was, suddenly, there’s so many people who are in your show. In one of the first series, we had Bill Nye, Martin Jarvis, Henry Cavill, who I had to give a kiss of life to – snogging ‘Superman’!

I could go through a long list of people who helped the show take off over the first season or two. Idris Elba was in one. We had so many people there, and I had some great advice from Jason Connery, who was a mate at the time. He’d been playing ‘Robin Hood’ on TV, so he knew about being in a series, and he said, “Nat, right now you are the pin up. Don’t become the dart board.” It was really clever advice.

And so one of the great things to do when you’re on set is always to make sure… so

I remember being in an Inspector Morse before I started my thing, and John Thaw was an amazing guy, but very insular. He’d do his stuff and that was it. I remember saying to him at the end of my first ever rehearsal on set with him and Kevin [Whately], “So, is it all right if I do that then? Do you want me to do anything different?” It was a three page scene of dialogue. He said, “You do your job, I’ll do mine, alright?”

So when I was doing my series in my little trailer, I had a fruit juice machine, I had sweets, I had everything I could possibly do for the cast to make them feel at home and welcome. And I don’t know if we ever reached the heights that John Thaw did, but that was my way of doing it. I love the process.

What was it like being part of such a long running TV show?

I think we did 25 shows, but they were an hour and a half each, so like films. I went out to Ireland to do The Twelve Dates ‘Til Christmas on Hallmark – fantastic series. When I was doing that, I turned up in Ireland and I stayed in this flat, and guess who just moved out? Leo Suter, who’s the new Inspector Lynley. How weird is that? I don’t know Leo. We’ve exchanged emails and wished each other an enormous amount of luck. We shared a role, and I’m sure he’ll be fantastic in it.

I was asked initially about that by the casting director, but I was rather put off because the first thing she said was, “Would you like to play his dad maybe?” And I had to point out that he’s a Lord. His dad died. That’s how he became a Lord. Maybe in a flashback? More than being in it, I’d like to direct one.

You’ve also been in some amazing feature films, like Stardust, The Last Duel, The Chronicles of Narnia: Voyage of the Dawn Treader. How does the set of a big budget film compare to television and theatre work?

[Voyage of the Dawn Treader] is on my CV, but I wasn’t really in it. Ben Barnes, who’s a wonderful guy, played the younger me in Stardust, and we said, “If there’s ever a time when you need a father or I need a son, let’s call each other.” And he was ‘Prince Caspian’ in it. He phoned me up and said, “Listen, they need a ghostly image of my father behind me, will you come and do it?” I was on holiday and they flew me back to get this mask of myself done so I could be this ghostly image for him.

When you’re doing a Lynley, if you’re running a show like that, you’re part of its creative process. Whatever you’re doing, there’s a time schedule. It’s a different feeling, but it’s equally enjoyable, equally challenging, and it’s fantastic.

What was it like to work with Ridley Scott on The Last Duel?

I just thought he was incredible. There was one scene we did where we had me and Matt Damon discussing the dowry for Jodie Comer, who played my daughter. I’d just been working on a Spanish film series where the director kept going, “Okay, you look here for three seconds, then you look up for five seconds and then you come around here for six…” I hated being told to look like that.

Whereas Ridley just said, “I’m going to focus on the background and I’m going to come to you two. But it’s a negotiation. It’s like a poker game, okay? Take your time. When you’re ready, speak.” The tension, the electricity, was just fabulous. I think he’s a genius.

What’s been your favourite role you’ve played and why?

I don’t know if I’ve played it yet. If I could pick one, I guess Henry the eighth because it opened some amazing theatrical doors for me with Hillary and Jeremy and Ben. But I don’t know. I want to find it. I’m looking for it.

Finally, what was the best piece of acting advice you’ve ever been given?

One I was given was Ollie saying, “Just listen to what the other person says and then you’ll know what to say back.” There was another brilliant piece of advice which I read from Olivier – who I also worked with in his last film, my first film, War Requiem, when he was being asked the difference between film and theatre, and he said, “Just be honest.” And that’s what it’s about. If you can persuade someone that you are telling the truth, then you’re succeeding, whatever medium it is.

Thank you, Nathaniel, for sharing your career insights and advice!

Nathaniel’s Insights:

- Listen intently to your scene partner, as their words provide the necessary response for good acting.

- If you lead a show, take responsibility for creating a collaborative and welcoming set atmosphere for your colleagues.

- Strive for honesty and truth in every performance to effectively persuade the audience, regardless of the medium.

- Be willing to accept roles for practical reasons, such as pay or lack of other immediate opportunities.

- When acting, focus solely on your performance and avoid the distraction of production or business concerns.

‘Ragdoll’ is now on at the Jermyn Street Theatre until 15 November 2025.

Nathaniel will be reading ‘The Waste Land’ at Wilton’s Music Hall on 15 and 16 December 2025.

Take a look at our website for more casting stories and interviews with performers, casting directors and agents.