Addressing safety, bullying and harassment in the acting industry.

On this big episode of The Spotlight Podcast, we discuss safety, harassment and bullying in our industry. Joining us, we have Maureen Beattie, performer and President of Equity, Wendy Spon CDG and former Head of Casting for the National Theatre, and Ita O’Brien, Intimacy and Movement Coordinator who has recently worked on Gentleman Jack and Sex Education for Netflix.

This is such a huge topic for the industry, and we talk about a variety of layers within it – from the nature of acting as a profession, to the culture on set and in the audition room, to wider concerns around what is asked for and when, as well as the more detailed aspects of performing an intimate scene.

We want to warn listeners that some potentially triggering language is used in this podcast.

70 minute listen.

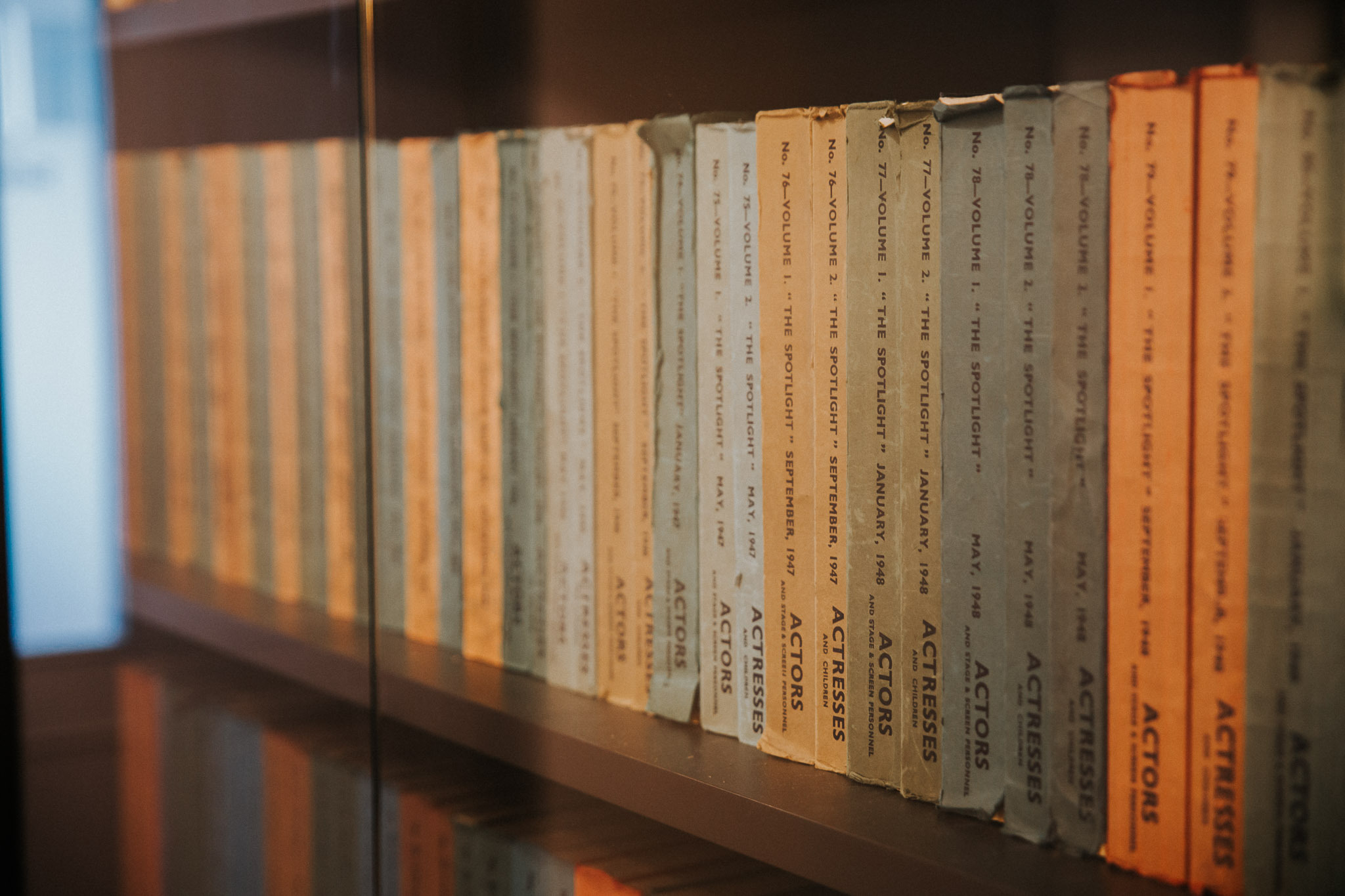

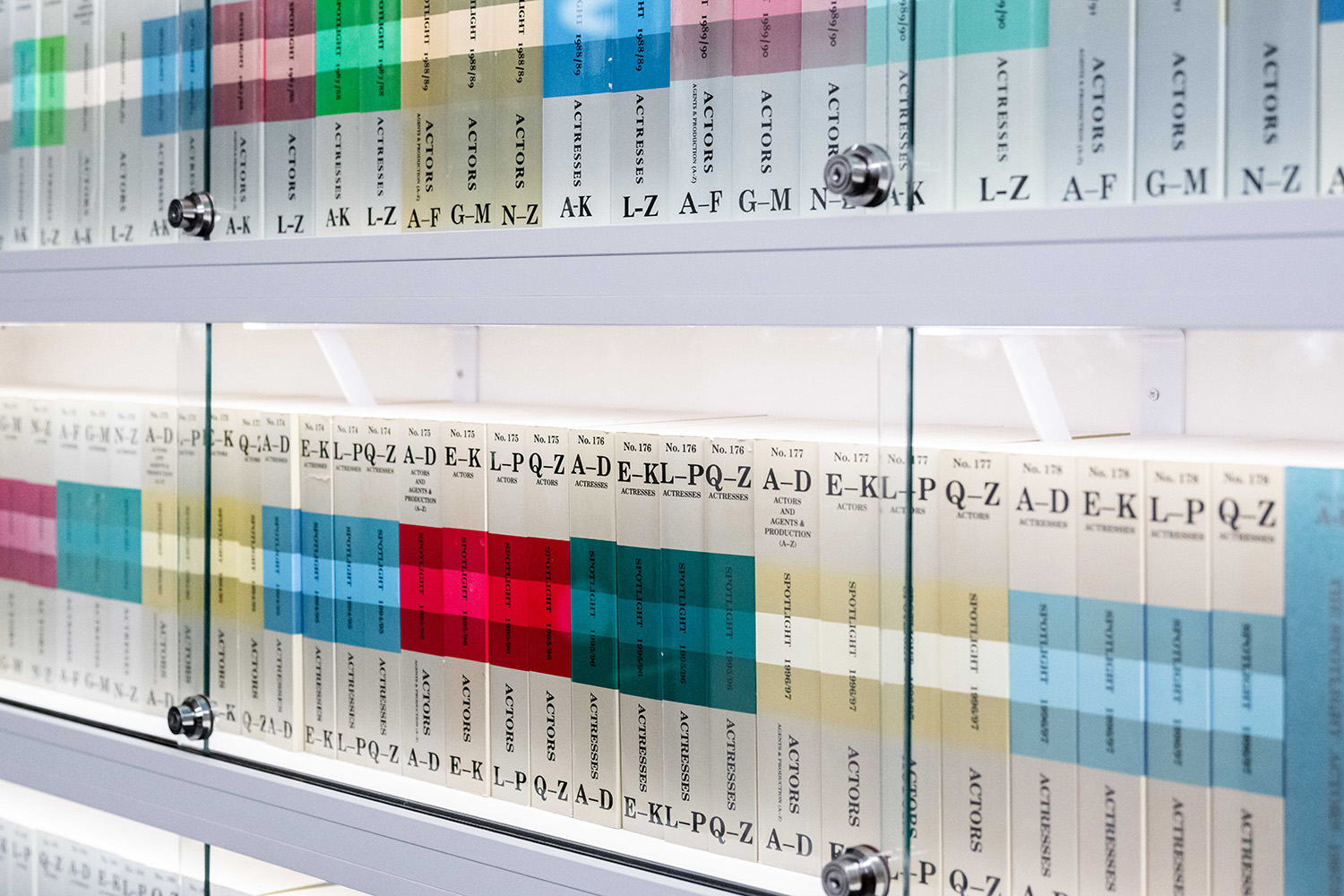

All episodes of the Spotlight Podcast.

Resources

Take a look here for more information on the discussion:

- Equity’s Safe Spaces Campaign

- Equity’s Agenda for Change

- Equity’s Harassment Helpline

- Ita O’Brien’s Intimacy on Set Guidelines

- ArtsMinds

- Samaritans

Episode Transcript

Christina Care: Hello, and welcome to this episode of The Spotlight Podcast. My name is Christina Care. I work at Spotlight and today’s topic is safety and harassment in the industry.

Joining us on today’s podcast. We have three incredible guests, including Wendy Spon CDG, former head of casting at the National Theatre. Maureen Beattie, esteemed performer and president of Equity and Ita O’Brien, intimacy and movement coordinator who has recently worked on Gentleman Jack and Sex Education on Netflix.

Needless to say, this is a huge topic in the industry at the moment, and we cover a wide range of issues within it from the way roles are auditioned through to the culture on set or on stage. And then we also talk in a bit more detail about intimate scenes themselves and how they’re executed. I want to warn listeners that some confronting and potentially triggering language is used in this podcast.

If you choose to keep listening, I hope you find this discussion as informative and fascinating as I did. Enjoy.

Christina Care: Maureen, Wendy, Ita. Thank you so much for joining us on the Spotlight Podcast. This is a really big episode, in my opinion, on a really important topic, safety issues with harassment or bullying. These are huge topics that are really being discussed right now in the industry and are really important for us to discuss as well.

I want to start by asking each of you a bit about sort of your perspective on the industry and how you think these issues have sort of manifested in the last years, perhaps Maureen, we could start with you as a performer. What do you see as the sort of key concerns for actors?

Maureen Beattie: Well, I think my perspective on this whole thing, whole situation has not changed, but widened over the past few years, because I’m now president of Equity, as you said, whereas before I would have been very conscious of the performers and how particularly obviously women, because I’m a woman, how we were treated within the industry, but as president of Equity, I am increasingly aware of the other people, obviously the male performer, how men and particularly young men are being bullied and sexually harassed now. And the vulnerability of the stage manager, the vulnerability of the assistant director, all these people, I just want to say that what we in Equity are trying to do is look after everybody. But I think there’s absolutely no doubt that as a performer, because of the very nature of the work we do, which if you are doing the work correctly, you remove a skin, you remove a layer of your cover piece that protects you in the world.

And in order to get at the emotional truth of the part that you’re playing, and that can be, if you’re playing somebody who is a murderer, we’re constantly asked to fall madly in love with somebody on the stage and you have too, for me the actors admire, I know that they open themselves to that emotional truth in a way that you don’t when perhaps you work in a bank. You’re not being asked to go we’ll I’m sitting here bank telling, and you’re doing a very important and good job, but nobody’s going. Or by the way, could you just snog that guy, who’s sitting or whatever it might be, but also it’s the emotional truth of it. It’s the feelings that it conjures up. And also of course in our business, you are often required to take off layers of clothing as well.

In Equity, we represent burlesque performers, for example. And one of the big problems we have is getting the public to understand that the person you see up on that stage, scantily clad doing an absolutely brilliant job of entertaining you, then goes into the dressing room, takes off that makeup, ties their hair back, puts on their coat and goes home to possibly their partner and children or their life that they just live with the rest of us. So for us, I think it’s absolutely true that we have a very in this… the whole world and in every, kind of business and every kind of industry now we are aware of the sexual harassment, for example, going on, I think our industry has a very particular problem with it.

Christina Care: Absolutely. And Ita your role kind of has become much more present, I suppose, as a result of these things coming to the fore. Can you tell us a little bit, what is the role of an intimacy coordinator? How does that contribute to act to safety? How did you get into that kind of work?

Ita O’Brien: Several questions in one there.

Christina Care: Yes.

Ita O’Brien: So, first of all, the basic strap lines of the role of the intimacy coordinator is it’s a role that invites open communication and transparency when talking about all intimate content and then putting in place a structure that allows for agreement and consent, and those are the two basics. And then those allow, the actor and the whole production to work with best practise. And it’s that shift to understanding. So again, Maureen, what you were saying is you bring yourself isn’t it to be intimate content, be nasty, your character to fall in love with somebody, to be possibly being naked because your character is making love with somebody.

Maureen Beattie: Absolutely.

Ita O’Brien: And my sense is in the past, there hasn’t been an understanding that actually an actor can also bring their craft to the scenes with intimacy as they have done with any other part of the play, or indeed a fight or a dance. And of course, a fight and a dance. Everybody really understands that it’s a physical choreography and you bring a skill. And so you have a choreographer that helps people to learn how to do the steps. You have a fight director that teaches someone the skills to look like you’re perhaps sword fighting, but it’s pretend. And before the open communication and before people being able to speak clearly and openly the sexual content, it was kept in that embarrassing place, so it wasn’t dealt with professionally and then the inference everybody does sex. So, that’s not a skill. And the difference is and people say why now? I mean, it’s like, it seems so obvious, but why now? And the difference is that with Me Too, that acknowledgement that, whereas with a dance you might be mitigating against possibly injury of twisting an ankle or a fight you’re mitigating against the injury of perhaps a sword poking someone’s eye out, the injury when the intimacy isn’t done well is over again, feeling harassed and abused with your personal and private intimate body.

Christina Care: Yeah.

Ita O’Brien: And post Me Too, people saying, being listened to and heard that time injury actually, can be physical, but also can be emotional and psychological actually is something to be really honoured and listened to. Actually those injuries and invariably have a way more ripple effects and can last in someone’s life way longer than a twisted ankle. And that’s now been listened to and heard, and then therefore producers are going and we need to put in best practise and we need to take care so that our productions are working to best practise. And also that then they won’t be open to litigation if someone says I’ve not been treated well.

Christina Care: Absolutely. And that’s where you come in to sort of provide that.

Ita O’Brien: Yeah, provide that structure.

Maureen Beattie: I must say, the point of several young actors, particularly young actors, I’ve never personally worked with an intimacy coordinator, I hope I’d get a chance to at some point, but, what they say is that it’s the difference between getting a bit carried away in a scene and it’s not that somebody necessarily is a bully and is doing it deliberately. But you get at this thing that you just said, but you’re just supposed to sort of do it nobody talks about it. Young people saying, that it allows that thing of going, no, actually we didn’t rehearse that your hand went there. Your hand only goes this far, and then my hand does this, and it’s a place that you can go where you can be absolutely precise like you would, as you say, with a sword fight, you go that sword was too close. That’s not what we’ve rehearsed. And it’s really empowering, particularly young people to go I’m sorry, that’s not it’s a precise think this is fantastic, really great.

Christina Care: Absolutely. It’s made such a change, I think. And it’s, as a result of these conversations that you’re able to be more specific, I think in a way that we weren’t able to be before or just weren’t doing right.

Ita O’Brien: That’s right. And actually it’s really lovely again, as I was saying, just coming back from Stockholm this morning, and one of the actors at the seminar said, that this work has made her realise that as an actor, she actually has autonomy over her own body. It’s such a basic thing, but it was a real revelation. And again, this inference that if you’re a good actor, then everything is in play and of course, that shouldn’t be the case. And that statement was beautiful.

Christina Care: For sure. Wendy, your point of view is obviously from a casting point of view, can you tell us a little bit how you think casting sort of contributes to that safety aspect?

Wendy Spon: Sure. I mean, essentially the casting director’s role is a sort of a mediator and enabler. Someone who, if you do the job well, you’re doing everything you can to ensure that everyone in the audition process gives their best. And that’s applies to both the actor and the director or producer that you might be working with. And I think, in some ways it’s basic practical stuff. It’s information and knowledge. It’s making sure that the person walking into that room, the vulnerable actor, because it’s never a level playing field. So you’re vulnerable on any number of levels. And obviously the way that Maureen described that so beautifully about, what you have to do as an actor, you’re taking a layer of skin off, you are making yourself vulnerable. And I think all casting directors are aware of that.

So, you’re endeavouring to create an atmosphere in a room which is constructive and respectful, Jonathan Kent – fantastic theatre director – as an ex-actor used to say, “The best thing I can do is make sure that the actor leaves the room with their dignity intact.” And I think that’s really important, but an awful lot of people don’t manage to do that. Sometimes that takes you into territory where the actor absolutely thinks they’ve got the job and maybe they haven’t, but because he’s so positive, so by extension talking about scenes of sexual nature, you have to give… If the project is sensitive or difficult, you have to be aware of that when you’re setting up the auditions and the process that you go through.

I had an issue recently where an actor was in touch about an audition that they’d done. It was actually for a charity, it was a promotional video for a charity but it was very, very difficult material. And they walked into the room, not knowing that they would be asked to simulate a physically violent act. And that was really interesting, it came to me via the Casting Directors Guild. And we sort of entered the conversation just to try and understand what happened and spoke to the casting people concerned because we felt that this person had been left very vulnerable. So I think those are the things where we can endeavour to make the situation as a safe as well.

Christina Care: Absolutely. So it’s not just the… There’s so many layers of this, basically we’ve already touched on them, it’s not just in the performance, it’s also in the audition room, it’s on set, there’s so many layers to that. Before we get into those sort of more specific scenarios, I wanted to sort of start more generally and ask you why it is you think there are these issues in this industry. I know that’s a really broad question, but what is it about this industry in particular that this is where we’re at, where we’re only just starting to have these conversations, because as you said, Maureen before, it’s unthinkable in a bank or any office scenario or most other conventional jobs, not even in an office necessarily anywhere, there’s a contract, there’s an idea of how things work, there’s a clear line of reporting and responsibility. What is it about this industry that makes it different?

Maureen Beattie: We’ll I do think that there are still people out there and there are far more than you might think who think that actresses are whores. I mean, they do. It’s extraordinary. I was at school a thousand years ago, but when I was at school, I went to a convent school and I wanted to be an actress was literally like, well, you’ve sold your soul to the devil that you, you’re a lost women. I mean, that was a long time ago, but it’s absolutely true. I do think that people still think of us.

And I do think there’s a massive problem, about the fact that the public, not all of them, but have difficulty telling the difference between the person they’ve watched on a stage playing a part and the person that, it just that it’s a person having a coffee down in the corner with the friends. I think there’s that. I think that the fact that our business is so precarious, people often say you need the hide of a rhinoceros to be a performer, for example. Well actually yes you do, but you also need to have a hide of a rhinoceros, which you can take off very quickly and remove a layer of your skin.

Christina Care: Yeah. There’s a perception, right. That actors are kind of both revered and are sort of separated in a way because they’re willing to do stuff that we’re not willing to do. There’s that sort of idea.

Wendy Spon: Well, I think that the other vulnerability, which plays into the specificity of our industry is the fear of being regarded as difficult and jeopardising future employment prospects. So if you stand up for yourself and say, “I really don’t want to do that.” The empowerment that’s come, I think in the last three or four years, straight out of Me Too, and onwards is brilliant because the boundaries have shifted, but there is that element to it. There are, as Maureen rightly points out, there are no sort of… you don’t have an HR company when you’re a freelance actor. And actually, UK theatre say that at least 45% of the industry is freelance.

Christina Care: Right.

Wendy Spon: So that means it’s very difficult to regulate. We don’t take up references. It’s maverick, it’s idiosyncratic. And so lots of behaviours have been accepted, that as again, as Maureen says, that would not be accepted in conventional workplace. That’s not to say that as we know sexual harassment doesn’t happen, we know it does. And also creative personalities are often challenging personalities.

Ita O’Brien: And part of the narrative with the intimacy guidelines when I started teaching them and they were saying, “well, how can I, when I leave here, say anything”, and I was saying to them, your first day of your training is your first day as a professional artist. And then also saying to them, you’ve spent thousands of pounds developing your artistry, hundreds of thousands of hours, and your artistry is something to offer to a production. So to think of yourself as an artist, and if you had a beautiful jewel that you’re going to be giving to a production, you wouldn’t let allow it to be trampled on. So to understand that’s actually what you’re offering. And then the other side of the narrative is absolutely that thing of everybody being afraid of ever, they say the word, no. It either means that they’re a diva or that are a troublemaker, and then absolutely that their job is in jeopardy.

So, the narrative right now, what I’m inviting is that shift to going, you are an artist, you’re a professional, and you’re going to offer your artistry to the best of your ability to serve the production. And the thing is that I started teaching this in 2015, and I knew that, that narrative was not a narrative that was going to be acknowledged as in the industry, but that’s where suddenly post-Me Too. And then where the Royal Court leading the way and being the first ones that came together, created a code of conduct. And basically the code of conduct is just saying that, and then the next thing is within the structure of allowing for agreement and consent, we’re inviting a positive no. We’re going, where of your personal and private body is at play, and also saying to them you’ve got to be ultra-aware, ultra-present. Yes. And so you can see your no. Not override yourself. Go beyond your own boundaries so that your yes can be trusted.

Christina Care: Right.

Ita O’Brien: Because what we want, I had a situation where I was on a production and I think one actor didn’t want to rehearse. He said, “I don’t want to make the sex scene a bigger thing that it needs to be.” I think the other lady would have liked to rehearse. So obviously I’m never going to ask someone to go somewhere that they’re not comfortable with. So it was no to going through the process, but it meant that that structure wasn’t put in place. A positive no, wasn’t part of the arena. And then the director, did the sex scene twice and they said, don’t have to do it again. Had lunch came back. Another setup we got, “Oh, actually I could have really done with, repeating that, but I’ve already told the actors, they don’t have to do it again.”

And I said, well, just ask them. He said, but they’ll just say yes. And I said, well, do you want me to ask them? He said, but they’ll just say yes to you, because they know that it’s come from me. And my realisation was the no hadn’t been present. And he didn’t trust their yes, to actually mean yes. And so he, as a director, he felt vulnerable that if he’d asked again that, then he would have been put upon them being declared as practically being bullying and harassing by even again. And we need to shift that, but it is shifting.

Christina Care: Sure. I just wanted to mention there that you’re referring to your Intimacy On Set Guidelines Ita.

Ita O’Brien: Yes.

Christina Care: And if anyone does want to read them, they can read them on your site.

Ita O’Brien: That’s right.

Christina Care: Can you tell us a little bit, just since we’re on that topic, how you developed them. What was what was the process of developing those guidelines?

Ita O’Brien: As a practitioner. My journey has been, I’ve been a musical theatre dancer, trended that to work as an actor, and then retrained to the MA and Movement Studies at the Royal Centre School of Speech and Drama. And then for the last, since 2007, worked as a movement teacher and the movement director. And then I was creating a play looking at the dynamic of abuse in our society. And I started looking at how I kept my actor safe. So that was the beginning of me putting in practises and processes. And that’s where most of the stuff didn’t know, the head of movement asked me to come and teach that work at Mountview.

And then as I started doing that, I also got support and some part of the guidelines come from Vanessa Ewan and her inspiration had been watching a fight call and seeing the time and the space and the skill that was given to the fight and going, this is what we need for the intimacy. And so, Vanessa’s inspiration absolutely formed the core. It’s number seven, where you go through the bit that I said, the process that allows for agreement and consent. Absolutely. It comes from Vanessa, I also found really good guidelines that spoke to the actor from Jennifer Ward-Lealand, who is the president of New Zealand Equity. So I’ve also worked very closely with her.

Christina Care: Absolutely. I think just what we’re sort of getting at, I think often in what we’ve been saying so far is the fact that we’re actually having the conversation and now setting in place some boundaries and some guidelines across different levels. So as an industry, as a whole, on set, as an individual, there are sort of levels to the boundaries that need to be formed. And that’s quite fascinating and quite new for this industry I think. I want to kind of shift topic for a second here and talk about the Creating Safe Spaces Initiative. Maureen, if I can pick up with you there.

Maureen Beattie: Yeah.

Christina Care: Where did that sort of come about? What were you hoping to achieve? Can you talk us through that-

Maureen Beattie: Sure. Again, back to the revolutions of, gosh, what was it 2017, November 2017, when we all just went, Oh gosh, thank God. It was like a boil that needed lanced, you know? And there we were in Equity, I was vice president of Equity at the time, and we just realised myself, Christine Payne and the other activists, we have got to do something about this. I felt at the end of this process, we had sort of spoken to virtually everybody who never worked in the entertainment industry, which was great. We spoke to people from the casting, we spoke to directors, we spoke to the filmmakers. We spoke to women’s groups, we spoke to drama schools, we spoke to writers. You can imagine. And we formed from that a three pronged attack and we gathered all the information and it was all put into a booklet, which you can get from Equity. I think you can get them from Spotlight. I think we tried to keep you supplied.

Christina Care: We do have them, yes.

Maureen Beattie: I’m the Spotlight supplier, and that’s called the Agenda for Change. And that’s the written, pre-see of all the different things that you can do as a practitioner and also the things that Equity are up to. And so we are still of course, lobbying the government to get things, put in that as I mentioned, of course of intimacy direction, talk about what drama schools could be doing. And all the different things, the BFI, the BAFTA people, all that sort of stuff, but it’s in this one so that’s your written word. The visuals are the poster campaign, which is the Creating Safe Spaces poster. And on it has the harassment helpline. And it also has our harassment email, which is harassment@equity.org.uk. Both of which I know if you send an email, it’s not completely confidential, but it is confidential in terms of it will go no further. And then along with that, that is now a new member of staff, who is on the end of that. Adaam Merali-Younger, absolutely fabulous.

Christina Care: We’ve got a podcast with him too, by the way, if anyone wants to listen to that.

Maureen Beattie: He’s terrific. And the third part of it, which has been massively popular and really has made a kind of astonishing difference is the read-out affirmation, which is a human being says at the beginning of every project, “This is how we are going to behave to another.” And of all the things, it’s the one that people go, “Oh yeah”, because, with all the jobs I’m doing – says she hopefully that it continues – I always call the director or whatever and say “Listen, would it be all right if I read out”, now I can’t remember the last time somebody said, “What is that?” Always the answer is “Oh, we’re going to do that anyway, oh you’ll be there oh, great you can read it.”

Christina Care: Right.

Maureen Beattie: And then it’s stuck on the wall, under the poster. And friends of mine have said to me, I was in rehearsal everybody was behaving themselves really well, then about a week in there was one guy getting a bit antsy or one woman behaving whatever I said, all you need to do is just point to the affirmation or indeed just read it all again. And people go oh. That’s basically what the Agenda For Change. Do you want me to say the words of the affirmation or-

Christina Care: Do you know them by heart?

Maureen Beattie: Yes, indeed. I do.

Christina Care: Yes. That would be lovely.

Maureen Beattie: Every single one of us working on this project is entitled to work in a safe space, a space free from fear, a space free from bullying and harassment of any kind. We will work together, honouring our differences and celebrating the gifts that we each bring to the table. We will treat one another with politeness and respect at all times. And if we are subjected to, or witness bullying or harassment, we will speak out knowing that our voices will be heard, and we will be taken seriously, together we can create a safe space.

And when that’s read out in a room, it’s absolutely astonishing. You can see people going… not that people are going, “Oh, I was going to behave badly and now I can’t.” It just really sits there in the air. So that’s the agenda. And that’s the main thrust of what we are… And we didn’t just do it and leave it there. We’re just about to start, because of course, one of the things were really keen to do is get the proof that it’s working.

So it seems to be working, but we’re going to do a bit of a survey and say to people, have you noticed a difference? A year ago what were you finding? Now, what are you finding. And that will also teach us how to improve and make it better. And we had a bit earlier on in February this year, we had a little do, Ita was there, to just honour the fact this has been created a year ago and to ask ourselves the question, what else do we need to do? And I’m sure we’ll speak about that.

Christina Care: Yeah, of course. I mean, for me, the affirmation is super powerful because it’s about accountability and responsibility. That’s making everybody in the room responsible. I think one of the sort of difficult points, particularly and I obviously have the great pleasure to talk to people like yourselves and a lot of different casting directors and producers and directors. And the thing often that comes up is, ‘Oh, I think it was that other person’s responsibility’. It was the person in the room I wasn’t in the room or the producer signed off on that or whatever it might be. There’s a bit of culture of, well, it was this other one other person over there.

Maureen Beattie: Yeah.

Christina Care: And I kind of wanted to yeah, plug into that a little bit more, obviously, acknowledging that we are a room of women here and we don’t represent every role that’s imaginable on a production set but what do you think the role of particularly, I want to ask about the producer, so maybe Wendy, it’d be good to start with you on that, because I think often once you’ve actually figured out what a role might look like, it’s up to the casting director to then sort of define in the room what might happen, would you agree? What is the role of these sort of external parties in your view?

Wendy Spon: Well, actually, I mean, we’re very much as a casting director, you’re very much at the front end of the process.

Christina Care: Right.

Wendy Spon: So, in some regards, I think what happens once the piece is cast is like slightly out of your control. I mean, often you might be a first point of contact particularly as I used to be, if you’re based in a building like the National Theatre, there’s a level of kind of pastoral care that comes your way and you tend to know the people involved perhaps quite well. I went to a really brilliant event at the beginning of the year, which the Federation of Entertainment Unions had organised, which was called Creating Without Conflict: From Disbelief to Dignity and the Casting Directors Guild were asked to attend. And it was a really, really, great event actually with Equity, the MU, the NUJ, BECTU, The Directors UK, the BFi, UK Theatre, The Writers Guild were all there and it was amazing. What was really, impressive about it was how all of those organisations were actively engaging with how to improve things, how to change the culture. So I think that those people are actually also beginning to define for themselves what is appropriate on a set or in a rehearsal room. The casting director in one regard has a sort of limited role to play at that moment in a project. Does that make sense?

Christina Care: It does. Yeah. I guess kind of what I was interested in is particularly how you set the tone in the room, because I honestly think that, particularly for a lot of younger actors, that’s their first experience, particularly of the power imbalance that goes on in the industry. That’s just going to be present in their careers. It’s usually with the casting director in an audition, it’s that format where they finally kind of come into contact with that disparity, if you know what I mean? So I kind of wonder, obviously, you’re very present in CDG, there are standards being built around what happens in the room, but what from your point of view, when you’re actually creating a breakdown, what does that process? Is there guidance? How do we integrate safety into that process to make sure that when the actor finally has that face-to-face experience, it’s a positive one?

Wendy Spon: Well, the Guild, as you know, has a code of conduct, which is available on the website. And every casting director who joins the Guild has to sign up to that code of conduct. And that lays out all the things that you might expect about how you treat actors, very specifically practical things about the process. Again, going back to my point at the beginning about information and knowledge and empowering people in the room. I mean, literally in the room, I think you’re monitoring all the time what the feeling is, what the atmosphere is. And doing your very best, to ensure that the actor feels okay, that they feel as comfortable as it’s possible to be when you’re basically in an interview for a job and everyone is always nervous.

And also, to remind the director or the producer that it’s a two-way street, that actor coming in the room might need to decide for themselves whether they actually want the job, depending on what level you’re talking about. And of course, as you rightly point out a young actor starting out their experience with an audition, it can be quite traumatic, but you do your very best to demystify that process. You make sure that if you know that they’re young and inexperienced, you make sure that you’ve spent time with them in the waiting room to relax them a little bit, say, “Oh, this director doesn’t do small talk. Don’t worry that doesn’t reflect on you. He spends maybe five minutes with you sometimes less, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t like you, or that you haven’t got the job. So you just lower your expectations, or don’t expect polite conversation because it will be a bit Bish Bash Bosh!” There’s a lot of with younger actors, there’s a loss of sort of trying to, as I say, demystify or sort of nurture them through that process. But it isn’t a level playing field. It’s very difficult, but you certainly… It’s interesting because personally, as a casting director, I have very rarely been in a room, I suppose I haven’t worked for the kind of theatres where… well I’ve mostly worked for the theatres where there are quite experienced directors. Directors who people respect and trust. I’m fortunate in that I’ve never veered into the territory where you’re working with someone whose behaviour you think is dubious. There might be some exceptions to that if I think really hard about it but most people, a lot of those people know how to behave.

Christina Care: Yeah, for sure. I’m curious, just sort of occurred to me about the influence of social media in terms of the casting process. Because I think particularly now, as we open up our ideas of who can play what parts? I want to ask you, a very sort of specific question here, which is about trans casting, because it occurs to me that is something that Spotlight has often struggled to help casting directors cast is particularly trans roles. And so they often end up on social media, casting directors posting direct to social media and asking, this is what we’re looking for.

And I just wonder what the take of the room would be on that in terms of the safety aspect, because obviously in that scenario, that person is casting, not at an environment like Spotlight, they might be casting in a home or somewhere else. But obviously they’re looking for a specific kind of performer and that’s quite important too. So I’m just wondering, what’s your take on the sort of clash between wanting inclusivity and wanting safety, if that makes sense. And how safe is it to cast on social media?

Wendy Spon: Well, I mean, not very, I would think. I mean, it would specifically answering your thing about trans actors. I mean, the National Theatre, as I’m sure you know, have just done a big event, which I participated in some of specifically for trans actors, which was great and that was about expanding our knowledge base, to access those people who might otherwise, as you say, be sort of slightly on the fringes in terms of process. I think, if you’re a legitimate, if you’re a casting director, if you are wanting to expand your horizons, then it was okay to use social media, as long as you apply the same criteria as you would to advertising through Spotlight. There have got to be boundaries that you understand about how you describe a role or how you articulate that you’re actively seeking a trans actor.

Maureen Beattie: I would never want to, as you can imagine, get in the way of any trans performer getting a job, but I do think that we just have to keep a real weather eye on it. And as Wendy says, the same criteria have to apply. There’s lots and lots of platforms that you can use to get the entire performing community of the UK for example, this is a growing part of our membership, but we have to protect them because they’re part of the membership that is often regarded by members of the public, they don’t know quite what to do with them because they’re not like the absolute norm and so we have to protect them. It’s like our black and ethnic minority community, all those things, they have an extra layer of the my goodness, the deaf and disabled, gosh, the stories that came out of that community when we were doing the work on sexual harassment were just, what do you do when you can’t hear? What do you do when you can’t hear what’s happening behind you, what’d you do when you can’t see what’s happening around you? What do you do when you can’t run up the stairs or run down the stairs? I mean, it’s really quite an eye opener.

Christina Care: Absolutely so complex, it’s an intersectional issue. Right.

Maureen Beattie: Yeah, absolutely.

Wendy Spon: But certainly, I mean, speaking specifically to your point about auditioning in someone’s home, I mean, again, the code of conduct for the Guild, that specifically sets, that we should actively discourage meetings in places that are not a professional environment.

Christina Care: Absolutely.

Ita O’Brien: But the other thing, there’s such a rise in the last 10 years is self-taping. One of my workshops that I ran, it’s actually done for all females, and people sharing their stories of intimate content, several of them were saying they got a breakdown and the casting said, “Oh, if you have your own latex, please, can you put it on.” And then “Please, can we be wearing a thong? And at the end of the script, can you turn and show your thong to the camera.” And again, I’m saying, if you are doing anything at all that you feel nervous, it’s overstepping your boundary, that’s belittling or making you vulnerable, you just do not do it. Again, your artistry is not worth that, but unfortunately more and more has been asked.

Wendy Spon: On the self-tape front? That’s really shocking.

Ita O’Brien: And part of the guidelines are, if you’re asked to do intimate or sexual content, It should be in the second call, so that you’re sent the script and you know, what the content is. And if you feel that you want an extra layer of safety, that you’re able to bring a chaperone with you, bring a friend with you that can be present in the space. And if that’s going to be filmed, then that you have a contract, you asked the casting to sign to say, “once that role is cast, that tape will be destroyed.”

Wendy Spon: I’m reminded of a story that I was told by an agent with a young actor straight out of drama school, who got a really, really big job. And it was both a big job and their first job. And it included scenes of a sexual nature, it included a storyline of incest and of course the scripts they weren’t properly finished. They weren’t all available when they accepted the job. And when he did receive the scripts and it became clear quite what was being asked of him, he was extremely uncomfortable and when the agent challenged it, she had to really enter a battle with the production company and the producers who threatened to recast him rather than change the content.

Ita O’Brien: With him? To be okay with the content?

Wendy Spon: Yeah. And in the end, because she took a very, very, very strong position, which she felt, interestingly going back to our original thing about the specificity of our industry, jeopardised some relationships that she would rather not have jeopardised in terms of employment opportunities for her clients. But she stood her ground entirely to her credit. And they changed things and they amended things sufficiently, but I think it was still quite traumatic for this young actor.

Christina Care: Yeah. But that brings up a very good point though, about something you said before Ita, which is about saying no, how you say no, can we talk to that a little bit more in terms of what does the actor actually do?

Ita O’Brien: On that same note, can I just finish off with a point, what I want to say about the self-taping. The thing is if you’re in a casting and you know it’s being filmed and there’s sexual content, you can have that contract and have that agreement consent that then will be destroyed once the part is cast. But when you’re sending a self-tape off, you’re not going to have that ability to have that signed off with a contract. And that’s what I’m saying to everybody do not send those self-tapes off with any content that you are at might be concerned about because if you don’t have control on it, it could end up on any social media.

Christina Care: Well, no, I just wanted to know, what your take would be. I mean, if, say for instance, someone actually got to the room, Wendy what would you say to someone if they actually got to the room and then were like, no, I’m not doing that. I just want to sort of demystify that for actors. Can they say it in the room?

Wendy Spon: Yeah, no, I understand. I think if it hasn’t been made clear to them in advance that they might be expected to do whatever they feel is in the moment is inappropriate, then they absolutely have the right to say no and both myself and the director should respect that. Because I think, you really can’t expect someone to do something in the room that they didn’t know about, It’s not right. I do think that sometimes these things are self-selecting, if you see a script, I mean, obviously I’m mostly dealing with extant scripts, It might be a new play, but it’s there, it’s in your hand and it’s unlikely to change so radically between you auditioning and being in it if you get the job. But I know with film and TV, it’s very different. But I think if you read the script and you feel uncomfortable, then you have to talk to your agent who might then talk to me as the casting director and ultimately you might have a conversation where the actor decides not to put themselves in the frame for that role, because they don’t feel comfortable. But to come into a room and be asked to do something that you didn’t know about, I don’t think that’s appropriate.

Christina Care: Right, that’s not on.

Maureen Beattie: I have to say that, as a performer, going into the interview situation, of course like all businesses there are reputations and there are casting directors that we all the whole community just go, fantastic. You go in there, they’re so on your side. They just want you to be safe and comfortable. They respect what you do, all that stuff. And there are other people who are famous for not being like that. And some people who just don’t seem to be particularly interested, which I think is interesting because we are the people who are putting the bread on your tables, but a lot of people forget that. But when you go into a casting and the casting director is one of the people whose kind of like, it is absolutely like having somebody on the bridge at Thermopylae for you going, ah no, you can’t come across here. Because they’re on your side and it doesn’t have to be said out loud, but it’s just the whole atmosphere in a room like that is utterly different. And I would say that 99 times out of a 100, you can tell when you walk through the door. And it’s not that something awful is going to happen if a nice atmosphere isn’t there. It’s not that you immediately feel incredibly vulnerable, but it’s just a kind of feeling of yeah, we’re all going to respect one another. The performer’s got to respect the people doing the casting as well, turn up on time, have your lines learned if you’re supposed to, whatever it might be. But it’s really, really important, that, that feeling the casting person is on the lookout for you if necessary. It’s great, it’s really good when you get that.

Christina Care: Absolutely. Do we think in general, there’s much difference between what gets asked for a sort of film role versus a theatre role. Do you think one is more… What’s the nature of the auditions in terms of what gets asked for.

Maureen Beattie: I think probably it would be true to say – I’d be interested in what Ita and Wendy think – but it’s probably true to say, that overall there’s a hell of a lot more nudity and sex on screens, television, and film than there is on say theatre and radio.

Wendy Spon: It’s such of a kind of storytelling, isn’t it? Essentially between theatre and script and screen. And the stakes, in some regards, the stakes are higher. They’re higher financially. They’re higher because that what they want is viewing figures. I mean, obviously you want to sell tickets in theatres, but there’s a different stress on that, I think.

Ita O’Brien: And, and I think very often in theatre, you’re going to look at a heightened or abstract way to represent sexual content because actually, well, first of all, if it’s just straight on a sexual act, past the fourth row, you’re not missing much detail anyway.

Maureen Beattie: That’s true.

Ita O’Brien: That’s certainly not what you would capture on camera. And invariably theatre is about representation of life and so it tends to be created a lot more artistically or the ideas of it and so therefore the vulnerability isn’t quite as full on. But certainly on film, you’ve got the idea of reality and actualness.

Wendy Spon: Yeah, naturalism.

Christina Care: Just to close out the audition kind of topic I wanted to ask about NDAs.

Maureen Beattie: [audibly inhales]

Christina Care: I had a feeling you might react like that Maureen.

Maureen Beattie: But there’s some great NDAs or some good and very important NDAs.

Christina Care: I’m sure. I just want to know a bit more, well, how do you think they’re misused?

Maureen Beattie: Well, they are just horribly misused and actually, you cannot use and anybody in our business, be they Equity members or not, who is asked to sign an NDA. An NDA that you sign cannot legally be used to stop you from speaking about something which is not legal. If somebody bullies you, harasses you or sexually harasses you, signing an NDA to say that you won’t talk about it has absolutely no power at all and please remember that.

I do understand that you might well still feel vulnerable and not want to be, as Wendy said earlier, about not being the one that makes a fuss and not being the one they say well she behaved, or he behaved like that or whatever, and should I say they behave like that and so we’ll never have them back. I get that as well, but it has no power at all. Do not let them fool you about that. So one of the problems with NDA is there are good NDAs. I mean, the job that I’m just about to start, I signed an NDA because nobody wants me to tell what happens in the plot. And that’s a really good thing because it’s a fantastic plot and you’re constantly going, “Ooh”, and that’s all part of it. I’m really happy to do that, but I’m not happy to sign an NDA that says that if somebody sticks their hand up my skirt I’m not allowed to talk about it. So we’re very, very conscious of it. And we just need to police it all the time.

Wendy Spon: I mean, they’re pretty much never used in theatre. And we use them at the National when we did the show about Rebecca Brooks, because it was during the trial. And so we had to have an NDAs with the script and watermark scripts and all of that, but I’m pretty sure it very really occurs in theatre.

Christina Care: Right. That’s interesting. I kind of want to ask then in terms of moving on past the audition process, once the actor has actually been given a script, how soon if they can see that there are intimate scenes in there that perhaps they’re unsure about, how soon are they able to actually talk about that? What would you recommend?

Ita O’Brien: I mean, part of my recommendation is, and I feel it’s asking both in theatre and TV and film, so there can be that open conversation and agreement and consent. And also just as you were saying, Wendy, that thing that the director getting the actor that is happy and comfortable to do the content that they have in their vision. And for the actor to know that they’re going to work with a director that they trust in order to create that vision in a way that they feel comfortable with. But that means asking the directors to think about that content earlier than they might’ve done. Thinking about it and then having that conversation doesn’t mean that it has to be locked down in stone or that it can’t change because of course, we’re in an industry where it is about responding to the people you have in the room, responding to what they bring creatively, and things can shift and change.

But to be able to have that conversation, clearly and openly about what it is you think you want. And as you’re saying about this young guy before they take the job, and I say to the actors, if you’ve been offered a job, great. If the director hasn’t brought that subject, and you can see that there’s intimate or sexual content, then you bring the conversation and they say, “well, how do we do that?” I say, well, contact your agents and say “Great, thank you very much, please can we set up a call or a meeting so that we could have that conversation” and I also say to the actor you be responsible. If you see that content there, then you make sure that you also prepare, perhaps do your research, have your ideas so that you’re not just coming in and go, “Oh, I don’t know. I’m uncomfortable.” You go in, as I say, as a fellow professional, empowered, be able to have the conversation, to be able to listen to also what the process of the director has and if you feel they don’t have a process that’s going to help you as the artist to give the best sex scene, that you offer the intimacy guidelines and as a solution, not a problem. And as a positive way to say, this is the way I’m going to give you the best intimate content that I can give you.

Maureen Beattie: I think that thing about agents as well, I think good agents-

Christina Care: We’ll, we’ve kind of omitted the agent here, haven’t we?

Maureen Beattie: Absolutely as part of that whole way of how do we protect people? And if you’ve got good agents on your side and you’re phone up and you go, listen, I’ve got this bit of a problem here. This thing, can I run it by you, maybe going to see your agent and you have a chat and everything like that, and then I mean, my agent would, if I said, “Listen, would you set up a meeting with whoever this person is? And would you come?” Absolutely no question. The agent is really key, again, like the casting director they’re on your side. And I am staggered to find myself meeting young actors who are afraid of their agents. I mean, frightened of their agents? This is the person who’s supposed to be out there working for you.

I was working at some point in the past few years with a young actress, and her agent wanted her to go up for this job where they said in advance, they wanted her to show, I think it was to stand in her underwear or something like that, she was really uncomfortable with it. Really uncomfortable. It was a proper bona fide production with a bona fide cast and whatever. And she was sharing a dressing room with three older actors who all went well, you just don’t do it. You’d phone your agent and you say, I’m not willing to do this. And she said, Oh, I wouldn’t like to and blah, blah, blah. So eventually she did. And the agent gave her a hard time, a really hard time. And we had to sort of nurture her through it and eventually she agreed that she would go in and she did it without taking her clothes off. The job didn’t work out, but that’s sort of neither here nor there. Well, maybe it is here or there, because maybe if she had, she’d have got it. I don’t know what the situation was… But I was really, on the subject of agents, I was really shocked by the fact that this agent was not absolutely without question on her side immediately. But of course, it’s that thing of the agent doesn’t want to get on the wrong side of people because they’re going to cast other people on their books and it’s all those things. But for me, the number one, you take somebody on, then you got to be their wingman.

Wendy Spon: It’s also quite a good advert for joining a union, because actually if you are a member of Equity, then you also have all of the support network.

So I was going to add something that came up in Creating Without Conflict event where, I don’t do you know, Sameena Zehra? She spoke very sensibly about confronting the small things. So mediating very early on. So trying to empower yourself, I mean, I suppose that’s part of it, what you were saying Ita about having the conversation very early on.

Ita O’Brien: Yeah.

Wendy Spon: So that the thing becomes constructive and positive rather than escalating to the situation that you described with the young actress and the three older actors having to nurture this person through something. And she spoke about, we don’t want to demonise people. Sometimes people have really good intentions and bad behaviours is one of the things that she said. So I think there is a level of education that needs to happen and we do all of us, including actors need to take responsibility for ourselves and for each other. And I think the shift in the culture that we’ve all witnessed in the last two or three years is enabling that. And we should celebrate that. And we should really encourage, particularly younger actors, to feel that if someone does something in a rehearsal room that they don’t like, rather than just biting their lip, they quietly and with the support of their peers perhaps just deal with it head on.

Ita O’Brien: And that’s, what’s so positive about the codes of conduct. And now I’ve been on productions by the code of conduct, are now read out at the beginning as long with the Safe Spaces at the start of either the rehearsal process or the first production meeting. And of course, other than just naming and having those words said out loud, about fundamental respect, which I completely agree have their resonance. Then also, the person is read out, who’s the person that you go to and the channels that you go through if you need redress. And that’s also such important difference that before the codes of conduct and therefore really clearly having the structure then of redressed, that’s where people were left going, well, I’m not feeling very happy, but who do I go to?

Maureen Beattie: Absolutely, yeah.

Ita O’Brien: And that’s also a part of what really empowers people that, that pathway is now clearly set out.

Maureen Beattie: Yes, the original gig economy, how do you do that? Because if you work in somewhere where you’ve been working there for 25, 30 years, there’s an HR person, there’s whatever, but you never know. And it’s a lot to ask of people and in fact. One of the groups of people that I’ve been very much involved with is a group that was put together by Sue Parrish, who is the artistic director, among many other things that of Sphinx Theatre Company, and Julia Pascal, the writer, producer, director. So one of the things we’ve not had a chance to do yet, but we’re hoping to do is start a kind of a guardian angels thing where there will be people. I mean, because I’m 65 now I’m getting a pension from her majesty, thank you so much your majesty and I don’t… I’m not extravagant so I can actually afford to have somebody go, “you know what, I’m never going to employ you again.” And I go, “okay, that’s fine. If you don’t want to employ me, I don’t want to be employed by you.” So I’m in a very strong position in that way and also we would hope to get people, men and women, who are in positions of power who go, “excuse me, you just can’t behave like that.” People who you can’t afford to not employ again and to get a thing where you sort of sign up and you go, I will be that guardian angel or whatever, we’ll think of something slightly catchier, and then you get a badge, a beautiful badge. And the idea will be that when you are in that room, you are declaring that you are happy to have people come and talk to you. And I think that is something we can do as well as the other stuff that’s going on. And have somebody like that in the room or nearby, so watch this space.

Christina Care: Yeah, for sure. I think that’d be very powerful just knowing exactly who that person is. I think, it would be remiss of me not to kind of ask for us to go into a little bit more detail about actually breaking down something that you need to do on set. And I was thinking in particular, Ita, maybe you could talk a little bit to something like a kiss scene. If someone is asked to do a kiss, what is your process or what would you recommend for breaking that down?

Ita O’Brien: Yeah, lovely, I’m glad you asked that. And it reminded me of one of the paragraphs we had in the guidelines, be aware of ‘just’.

Christina Care: Yes, exactly be aware of just.

Ita O’Brien: Whenever someone says, “just…” you already know there’s going to be bad practise in place. And invariably with the kiss it’s like, “Oh, it’s just a kiss.” And the thing is that, of course a kiss is never just a kiss, it’s there because it’s telling you something. And is it a kiss… I’ve been working with a trailer recently: he kisses her, she pulls away. He kisses her, laughs it off, she breaks away. That’s really clear beats, really clear power play. I mean, you want to honour that, and when you honour that, oh my goodness, do you get something really exciting. It’s telling you about character, it’s telling you about, what the power play is within those moments and you want to honour all of that.

So, the first thing with the guidelines, in order to really keep it professional and not private. So often historically we’ve had that thing of the director might talk really clearly about the intimate content and then say, as you mentioned earlier on Maureen, now you two go and work it out for yourselves and suddenly you’re no longer professional, you’re in a private space. You’re two individuals and when you don’t have an outside eye that’s making sure that you’re serving character then you’re left scrambling to go, “Oh, what’s all right for you.” And “this is what I like…” so, none of that. One of the first steps of the process of the guidelines is always have a third person present. If the director, perhaps might’ve spoken about it and they want to carry on with rehearsing something else, ask for the assistant director or the stage manager or if you’re on set, a second AD or the last resort is at least to have a fellow actor with you.

Then it’s getting an agreement and consent. So it’s always serving the writing, it starts from really looking at, as I said, what’s the power play? What’s the beats? Which will already give you the basic shape. And then you agree touch. So, “Is it okay if I place my hands on your cheek?” And then you do it. And again, this is where we’re offering, inviting a positive response. When I say a positive response, it doesn’t mean it has to be yes, but it’s a clear yes or a no.

Also we’re looking for what’s in play body parts-wise that that actors are completely comfortable with. So that when they then take those body parts into serving character, that they’re open and free and not in that place of shifting to the personal body where they’re concerned. This is where I say, your ‘yes’ is your yes, your ‘no’ is your no and your places of ‘maybe’ is a no. Because as soon as you go to ‘maybe’, you’re already having tensions.

Once you’ve got that agreement and consent, and that’s where then you’re asking again… actors were saying, “I so often actually override what I really feel in order to be pleasing.” So it’s really inviting you to really body listen and be really present. Then once you’ve done that, it’s like a dance and we know what’s in play: I gaze into your eyes, I step forward, I place my hand around your waist. And then she might say, I place my hand on your cheek, I lift my chin, we kiss. So you repeat it and it’s absolute structure.

I had a beautiful director yesterday and she was going, “but I like to improvise and they’re not free.” And of course, the structure, what it does do is just like any dance as you’re learning that physical choreography, it can look a bit stilted, but once you’ve got that frame, then you go back re-anchor the emotional journey, get that clarity of; she’s waiting there nervous but absolutely delighted of this finally coming together, the man in his sexual energy coming forward, pulling her towards him. She lifts her hands on the cheek, she floats up as she lifts her chin and they kiss into a beautiful-

Wendy Spon: Can I ask Ita a question? Do you ever… So that doesn’t surprise me about the director, do you ever get resistance from actors to the choreographic nature?

Ita O’Brien: Yes, as I said, particularly older actors go, “I know how to do this. I don’t want to talk about it. And I don’t want to make it a bigger thing than it needs to be.” And of course the irony is that when you deal with it and you speak about it openly, you talk about it an actual adult ways. One of the things we’re inviting is to not use language that infantilises, titivates or objectifies. So you’re not saying, “Oh, your tits” or “your one-eyed trouser snake.” You talk about breasts and penises so keeps it professional. And it allows you to bring your craft of the actor to the intimate content, but yes, I’m absolutely up against it. That’s where buffering that resistance.

The other thing is putting in a timeout. Timeout is so important. So not only the director, but it gives the actors the autonomy to halt the action. I was doing a play called Food, this particular character, her storyline is at 14, she’s assaulted by other boys. 16, she gets drunk at a party, she thinks she’s going to go with one guy, but actually all these other guys turn up at this bar and she’s gang raped and it’s observed by her sister that narrates it. And then later on she’s raped by her mother’s boyfriend. So that’s quite heavy, isn’t it? Emotional content for that actress to go through. So when we we’re choreographing the gang rape.

Christina Care: I have seen the play go on.

Ita O’Brien: Did you see it?

Christina Care: Yes, I did go on.

Ita O’Brien: So again, it was abstracted. We had the white goods, we had like a fridge and a cooker, it was abstract her acting this out but we had to really analyse the text, go, okay, Tom does this. And then Harry comes in and does that. And so that was absolutely a time where we did a certain amount and the actress thing go, okay, you need a timeout, need to go and take some fresh air.

And then in particular on set, I’m calling a timeout or having that so once you’ve rehearsed it… I make sure I have a really good relationship with the first AD so that you call out the close set and then very importantly, you’ve agreed with your director, with your actors, your timeout. It might be a physical sign. It might be a word. But that’s also shared with the whole of the crew, so that the actors know that at any time, if they need to, they can call a timeout. So for example, if you’re doing intimate content, it’s natural and normal if you’re doing rhythmic movements up against each other, that you might become aroused. However, for lady it’s not so obvious, for a man it becomes obvious however, it is not suitable to be in the workplace with an erection so that’s absolutely one of the times that you’d call a timeout.

Maureen Beattie: Yeah. I have to say what you just said makes me want to weep with joy.

Ita O’Brien: Yay.

Wendy Spon: I can’t imagine, if I was an actor I simply wouldn’t know where to begin and I would be terrified and to have someone like you on set or in the rehearsal room with me would be so unbelievably reassuring. I’m amazed that this role hasn’t existed before. Everything you say about how much attention we give to choreography or to fight direction makes perfect sense in this context. And I think it’s a brilliant.

Maureen Beattie: And as you say that thing of just because it’s sexually intimate or physically intimate does not mean that it’s other. We’re telling the story, and then there’s this place where everybody goes to planet Zod and does sexy stuff. And then we go back and we tell a story. Like that thing you’ve just described so beautifully, the whole thing of the tentative first kiss, does she want to be kissed? Does he wants to be kissed or wherever what’s going on there? Or that would they be a bit embarrassed, as you say, it’s part of a story that you can tell. And if you tell the story right people are compelled by it. It’s just fantastic Ita, just wonderful.

Ita O’Brien: And then once you’ve got that structure, you can have-

Wendy Spon: It’s like playing a musical instrument isn’t it? You have to learn the notes and then you could be free with it.

Ita O’Brien: I had a scene I was doing in Dublin and there was a grab of the breast and then a hand right over the vagina, the genitalia so it seemed really full on. But once that’s agreed and consented to, it’s as nothing cos they know what’s going to happen. A beautiful scene. Then they decided to start it, they’d come in through the door and she was saying, “actually, I was more fumbling about coming in through the door.” The whole physical content she was really comfortable with and the director was saying, “Oh my goodness, once it’s choreographed, I can then get on with my job.” I’ve gone “right, now up the vulnerability” or “up the passion”, because again, you’ve got the frame and you can still have it different every performance, but the structure, the physicality is known, the actors are personally safe, so they can artistically then give their full acting that in character.

Wendy Spon: It also, am I right in saying? That it also pushes out of the room that kind of, what possibly some people became actors so that they could indulge that kind of, like the frisson that happens between two people and you’re sort of have this accelerated process of getting to know each other when you work as an actor. And I think it’s just great that you can push that out of the room by making it very choreographed and precise without undermining the authenticity.

Ita O’Brien: Absolutely.

Maureen Beattie: May I ask you, Christina. Did you feel when you went to see the play of where this terrible series of sexual assaults happened, were you sitting there thinking, well, I’m not convinced. I mean, I gathered it was done in a non-realistic way but did any of it bother you?

Christina Care: No, I have to say, I mean, it took me a little while as you were describing. I was like, I have seen that because I thought about it. I was thinking it didn’t come across to me as brutal. It was obviously a really difficult subject matter, but I was completely convinced by everything I saw. As you said, it was slightly abstracted, so it wasn’t literal. And I came away with a really interesting experience of a play, I didn’t feel… And I have to say as well, I was right in the front row. So it wasn’t like I was sort of detached from the stage, or whatever I was really right up in it. I think you did a marvellous job because it was a heavy play. But it came across-

Maureen Beattie: There you were. There was no feeling that you’d seen the work of an intimacy director.

Christina Care: Absolutely. I didn’t go away thinking, something is been undermined here or this is not real or whatever, not at all.

Ita O’Brien: Well, again, it’s so brilliant. I’m so glad. And of course that’s the irony and that’s some of the concern in the industry. And again, old school directors who are used to being, of power, to feeling concerned that their power or their autonomy of their direction of that moment is going to be taken away from them. And again, I say, well, you don’t think so if you’re bringing in a stunt coordinator or a fight director that your direction is taken away. You know, that they can listen to what you want. They’re going to put the safety mechanisms in place. So that you’re going to get really exciting fights. It’s exactly the same. It’s just our safety mechanisms are perhaps genitalia cushions and nipple covers, so yeah.

Maureen Beattie: A lot of people are worried about the idea, is this whole Me Too movement going to stop people being able to flirt with one another. Of course, it’s not going to stop.

Ita O’Brien: It just can still happen in the bar. It’s just not a work-

Christina Care: I know we don’t have infinite time, so I want to sort of wrap up some of our questions here and ask perhaps a slightly silly, provocative question. I don’t know. You can tell me, but do you think acting can actually ever be safe because you’ve talked about taking off layers and being vulnerable? I mean, I think I know kind of what the vibe is in the room in terms of how you would answer that, but I just kind of wanted to phrase it that way: can acting ever actually be safe?

Maureen Beattie: I think it can. I absolutely think it can. And I think, with all due respect to everybody, keeping it professional and changing the culture. You said this, you used the word culture earlier Wendy absolutely. We’re in the long haul here changing the culture of the way that our business is so that when you are in a room and anything happens and it feels a little bit uncomfortable to either you or somebody else and you see somebody else in distress… what we want is for it to become so unusual that you literally go, “did you see that? Did I imagine that?” As opposed to the past, which was well, it’s just was everywhere. So we’re on that journey now, and I absolutely believe we’re going to get there so that’s my take.

Wendy Spon: That’s good. I mean, yeah. I don’t think you’ll ever remove what Maureen described right at the very beginning about how you are part of being an actress, making yourself emotionally, philosophically, psychologically vulnerable. But with regard to this specificity of sexual harassment or bullying or whatever, then I think, yes, it can be. And we’re all, those of us that care, which is lots of us, we’re working towards that. It’s a vulnerable profession, it’s not easy to be an actor. And as I get older, I have more and more admiration for actors for everything. I mean, everything that you’ve been describing, Ita, about how you create those scenes, I’m sitting here thinking I’m so glad that’s never going to me. It’s a really brave thing to do. So we have to acknowledge that and make it as safe as we can, but it still requires you to be quite brave.

Ita O’Brien: And I want to carry on then from that thing of being brave. Because that’s part of what’s been levelled at actors is that, Oh, you’ve got to be brave to be an actor. And that bravery means you have to do any nudity content and any sexual content and actually that’s not the case. You don’t know what someone’s life has been up until a particular point. And if they’ve got particular places that are no go areas or particular places that are triggering, to be able to call them so that you can then still bring your craft of the acting, that’s what we need to take care of.

Maureen Beattie: We’re on the track, doing our best.

Ita O’Brien: We’re on the track, absolutely.

Christina Care: Vvery last thing. If someone is feeling uncomfortable, they’re in a job tomorrow, they’re in an audition tomorrow, what do they do?

Maureen Beattie: Well, if they don’t want to say it out loud to the person because they are concerned about being thought of as a troublemaker, as soon as they possibly can, as soon as they leave the room, If you’re a member of Equity call the Equity helpline. There’re all kinds of help. There’s ArtsMinds out there. If you’re really, really bothered, The Samaritans. And if something really unpleasant happens to you call the police. You’re allowed to call the police, that is what they’re there for. So, pick up a card from Equity, we’ve got all these different things on it and you can find it in other places as well. But the most important thing, say it out loud as soon as you possibly can to somebody and instantly it becomes more manageable. That is just a fact.

Christina Care: Absolutely. And on that note, thank you so much, ladies.

Maureen Beattie: Great pleasure, thank you so much.

Christina Care: If you’ve got questions about today’s podcast, please get in touch with us or talk to us on Twitter @SpotlightUK.

If you ever see a breakdown, you’re not sure about please hit that report button and we will investigate. For other information about how you can get help, please check out the resources section higher up on this page. Thank you for listening. That’s all for now from the Home of Casting.

For more information, take a look at our News and Advice section, and our guide to auditioning safely.

Episode originally recorded in June 2019.