The triumphs and challenges of working as a deaf actor, and the importance of deaf representation in the performing arts.

My name is Nadia Nadarajah, and I have over 16 years of acting experience in theatre, American TV series, short films and a mockumentary. I’m a fully deaf BSL user and I very rarely use speech.

On one occasion, I used my voice in a classical play because the director wanted a character with a deaf accent. This was cleverly thought out – my character used SSE (Sign Supported English, where we sign exact English word for word), which allowed the deaf audience to hear what I was saying, while my character’s sisters repeated what I’d just said in a teasing way (as sisters do) so the hearing audience would also understand.

This is just one of the many creative ways you can play with a character who may be an oral deaf character, a BSL-user character, or a character who is deaf but does not sign. It’s one of my favourite things to do – I love playing with lots of different ideas for deaf characters!

Using Interpreters and BSL as a Performer

To do my job professionally, I always book interpreters throughout my projects. For filming, I book an interpreter throughout the whole process. For plays, I book them until Press Night, as throughout the whole process, the cast and crew pick up and learn BSL and become deaf aware, where we can look after each other. Some cast and crew members are so intrigued and motivated that they go on to learn BSL Levels 1 and 2. I have VRS (Video Relay Service) as backup in case anything happens after Press Night. This lets me call an interpreter on my device and they can interpret from there.

I usually teach Deaf Awareness on the first day on set, as many hearing people have not worked with a deaf individual before and might feel nervous about communicating with them. After teaching Deaf Awareness, I found that the cast and crew felt a lot more confident about working together, making the whole production run more smoothly.

When helping a writer with their play, I usually book two interpreters to sign the lines as I listen through my eyes because I am deaf and British Sign Language is a different language to English. There are grammatical distinctions between BSL and spoken languages like English. BSL has its own grammar structure and syntax. For example, in BSL, word order, facial expressions and non-manual features play crucial roles in conveying meaning – whereas in English, word order and spoken words are the primary conveyors of meaning.

When I read English, it plays out differently in my mind, so I rely on the interpreters to translate it into BSL to better understand the lines.

When doing a read-through, we always form a circle or a semi-circle so I can see everyone in my peripheral vision. I then ask the hearing people to put their hands up if they are speaking so that I know who’s speaking. When it’s my turn, I ask the director if they want to watch me sign my lines or have the interpreter’s voice over. Interestingly, the directors typically want to watch me sign rather than listen to the voice over.

Rehearsing with a BSL Director or Consultant

When it comes to rehearsals or TV shoots, I always enlist the expertise of a BSL director or consultant to ensure accurate BSL translations. I have no issues exploring my character’s motivation, intentions, emotions, etc. The BSL director/consultant is there to work with me – going through the lines and making sure the translations effectively portray what the English is trying to convey.

The BSL director/consultant does not take over and change the lines, but they do check that the translations convey the message. We do these pre-rehearsal or pre-shoot to save time and book an interpreter if needed (i.e., there’s a hearing person in the room).

The Representation of Deaf People in Media

The representation of deaf people has grown over the years and I want to keep it that way. It’s an invisible disability and an important one for people to see on stage and screen.

Many deaf children are born to hearing parents, and the parents may be worried about their deaf child’s future. Their child might also be the first deaf person they have ever met, so when there is representation on stage or screen, it gives the hearing parents hope. They see the deaf person doing well and realise their child will be fine. They are just deaf.

There is a lot of focus on the medical model and the ears that do not hear, which means the cultural model is often overlooked. We are a language minority—we have a language, a culture, a community, and an identity.

The sad truth is a lot of hearing parents are not able to communicate with their deaf children because of the medical model. It often recommends the parents of deaf children not to learn BSL, which is so frustrating as there is evidence of BSL enhancing learning and development. A lot of the time, the parents just put their deaf children in front of the TV and have the captions on, but the children are not able to read at that age. Some programs have special screenings for BSL Week, Deaf Awareness Week, or International Week of Deaf People, but that’s only three to five times a year. We are deaf all year round!

The Use of BSL on Stage and Screen

As someone who was born deaf, doesn’t speak, and is strongly involved in the deaf community, I would love for there to be more representation of BSL users on screen and stage. I see a lot of deaf people on screen or on stage, but most of the time, they are not using BSL and are oral.

I love seeing deaf representation and applaud them every time, but I do feel sad sometimes that they are missing out on a language, community and culture. I do not want to see the BSL Deaf community hidden or for there to be a sense of shame around using BSL.

However, it has been a very exciting year this year, as there has been a growth in deaf productions and projects involving many deaf people. This just shows that having a different language is not a barrier. Also, as a coloured woman, I would love to see more representation of coloured, deaf individuals on screen and stage.

This summer, I will be playing a lead role at Shakespeare’s Globe in a play called Anthony and Cleopatra. I am in the older generation of actors, and when we were trying to cast ‘Anthony’, we realised this was difficult, as the character needed to be hearing but also be somewhat fluent in BSL. This made me realise the difference between the older and younger generations. In the Anthony and Cleopatra cast, the younger generation of hearing actors can sign and are very deaf-aware because there is a growth in understanding and awareness of deafness.

Back in the day, the attitude towards deafness was very limiting. It was mostly, “Oh, deaf people can’t do this,” or, “We don’t know how to work with someone like you,” or, “I can’t learn how to sign.”

We are seeing a growth of good-quality BSL among hearing people. It’s always the right time to learn BSL, especially now when it is growing and in demand. If we do Anthony and Cleopatra again in 20 years, I’m sure we will have no issues with casting and hearing people with BSL.

Nadia in the promo image for ‘Antony & Cleopatra’ at Shakespeare’s Globe / Image credit: The Other Richard

How to Support Deaf Performers

People like me need interpreters in auditions and on set, and I like to have my preferred interpreters. Deaf people do have a right to pick their preferred interpreters for many reasons, such as safeguarding, gender, preference for coloured interpreters, age, health reasons, etc.

For example, I am currently going through pre-menopause, and I would much rather have an older woman interpreting for me, as they will be able to empathise, understand what I am saying, and interpret efficiently as they go through it. I wouldn’t want a young interpreter in this situation who would not understand as they have not gone through menopause.

When I work with makeup artists or hair stylists, I like to have an interpreter who is coloured. They know what I mean when explaining my skin colour and hair texture. I have a slight afro and my hair is curly. The interpreter would be able to interpret smoothly as they are similar to me.

Lip-Reading as a Deaf Performer

People need to be conscious of lip-reading, as not all deaf people can lip-read. Lip reading is tiring, as we are constantly focusing on what is being said.

There is a system for understanding lip patterns. First, we work out the vowels and create the words in our head. Then, we can work out the topic and try to lip-read the whole conversation. It would take about three to four minutes to finally figure out what is being said.

Please do not expect us to understand everything and please do check in with us. There is a thing called ‘concentration fatigue’ or ‘listening fatigue’, where we become tired easily from concentrating hard and using our eyes. Hearing people do not have to rely on their eyes as they have their ears. Try watching something for 10 minutes with no sound and let me know if you’re tired or not!

Resources for Deaf Performers

Access To Work (ATW) is a programme run by the Department of Work and Pensions to support disabled people and those with long-term physical or mental health conditions in obtaining ‘reasonable adjustments’ so they are not disadvantaged when doing their job. As deaf performers, we have a right to participate in this program.

Productions often do not include a budget for accessibility and often do not have enough money to cover the costs of interpreters, as they can be expensive. This is where ATW comes in, which can cover half of the full costs of the interpreters.

Some deaf people prefer using captions, so book a closed captioner instead. The closed captioner works remotely and types what is being said amongst people, which the deaf person then relies on.

From all of us at Spotlight, a huge thank you to Nadia for sharing her insights with us!

Take a look at our website for more industry news and advice, including working with BSL consultants and Maria Miles’ account of acting with multiple sclerosis.

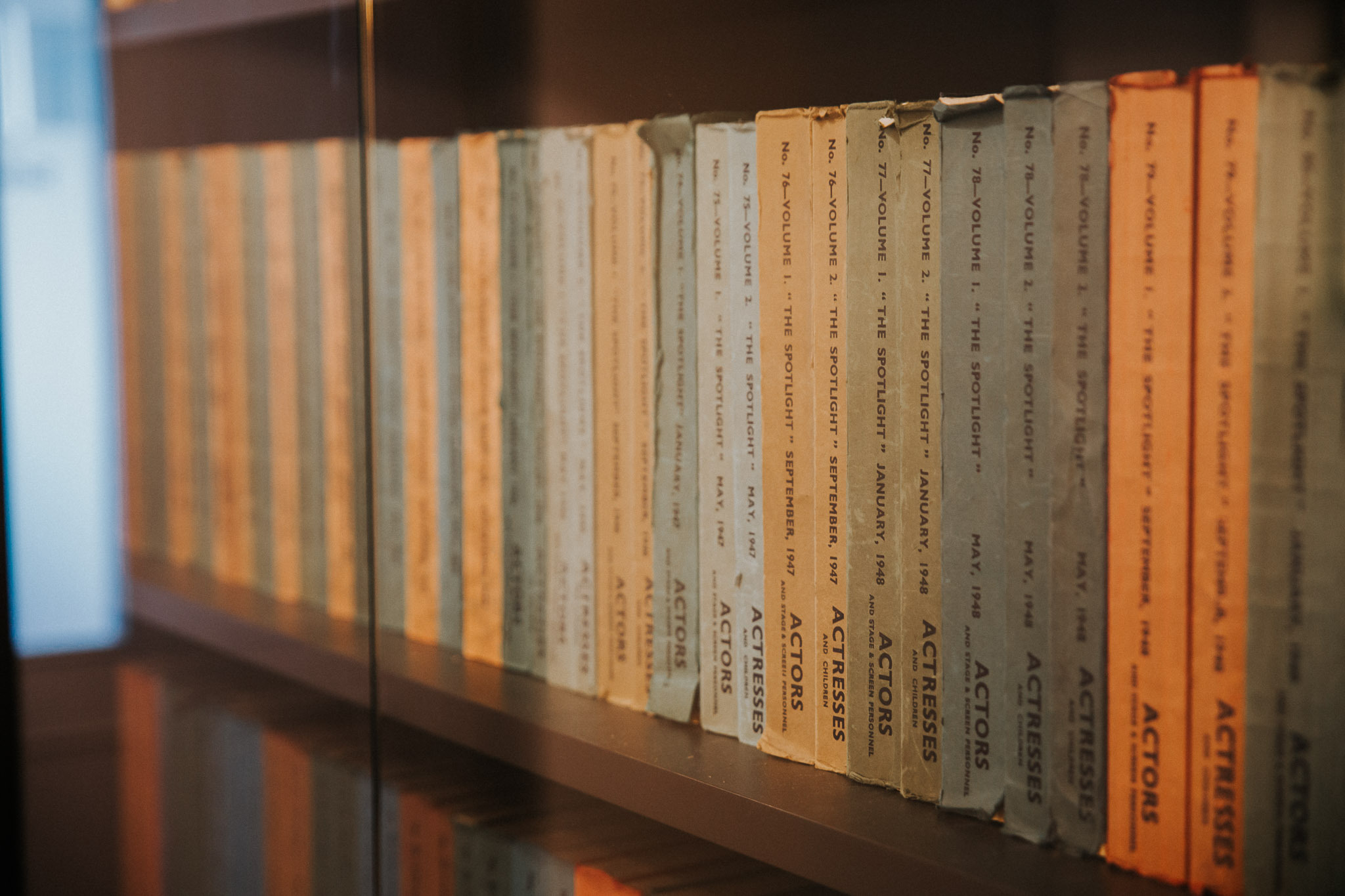

Nadia Nadarajah is an actress who uses British Sign Language. She trained at the International Visual Theatre in Paris in physical and bilingual acting. She was also part of Deafinitely Theatre’s Creative Hub training scheme. Her credits include: Vampire Academy, See Hear, EastEnders, The Hub, One More Minute, Meet at the Edge, and Anthony & Cleopatra, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Love’s Labour’s Lost and Grounded for Deafinitely Theatre.

Nadia Nadarajah is an actress who uses British Sign Language. She trained at the International Visual Theatre in Paris in physical and bilingual acting. She was also part of Deafinitely Theatre’s Creative Hub training scheme. Her credits include: Vampire Academy, See Hear, EastEnders, The Hub, One More Minute, Meet at the Edge, and Anthony & Cleopatra, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Love’s Labour’s Lost and Grounded for Deafinitely Theatre.

Headshot credit: Becky Bailey