Watch an exclusive panel with filmmaker Coralie Fargeat and casting directors Lana Veenker and Marina Wijn about the artistic collaboration between filmmakers, actors and casting directors.

At this year’s Berlinale, in partnership with Filmmakers Europe, we hosted a special private screening of the Oscar-nominated film The Substance, followed by an exclusive panel for Spotlight members.

The exclusive panel, moderated by Marta Balaga (Variety) with Coralie Fargeat, Lana Veenker (President of International Casting Directors Association) and casting director Marina Wijn, explored The Substance and discussed the art of casting and its creative impact.

The event marked the European Film Academy and International Casting Directors Association (ICDA) partnership announcement by Lana Veenker and Fatih Abay (European Film Academy) and the launch of the European Film Academy Casting Award, recognising casting directors’ vital role in cinema.

Topics covered include:

- The creative casting process for The Substance and signing Demi Moore.

- An insight into how filmmakers work with the cast to bring a vision to life.

- The portrayal of women on screen and what needs to change.

Watch the full panel discussion here:

About the Panellists

French filmmaker Coralie gained recognition for her debut feature film, Revenge. Coralie wrote, produced and directed The Substance, earning her three Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Original Screenplay.

Lana Veenker is President of ICDA. Based in the US, Lana’s casting credits include Trinkets, Paranoid Park and Wild.

Marina Wijn has worked as a casting director for almost 16 years. During her career, she cast over 80 feature films and series. Her latest project, Our Girls, will be out in the spring.

About the Film

The Substance is a feminist, body-horror thriller about a fading celebrity who takes a black-market drug that creates a younger, better version of herself. Starring Demi Moore, who was nominated for the Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role award at the Oscars 2025 for the role, The Substance critiques misogyny and the objectification of bodies.

Q&A Transcript

Edited for clarity.

Nobody expected Demi Moore to make a film like ‘The Substance’. Was it difficult to convince her to be a part of it?

Coralie Fargeat – The casting was a very long process. I knew from the start, when I was writing the film, that it was going to be one of the most challenging parts of getting the film made.

There is a financial reality of film that if you’re asking for a certain amount of budget, you need to have a casting that’s going to convince the financier. When we started the casting process, we sent the project to the first [actress] I had in mind, who was not Demi, and for six months every actress we sent the project to said no. It was a very untraditional project that was confronting the actresses to probably [face] their worst fear. So, I knew it wasn’t going to be easy to find the right match.

While we were exploring the part of ‘Elisabeth Sparkle’, I needed to start exploring options for ‘Sue’ because they are one – they go together. It was a very jigsaw[-like] process because until I had found who would be Elisabeth Sparkle, I couldn’t know who would be able to do her other side. I wanted [them] to have some sort of physical resemblance, but I didn’t want them to match exactly, so if Elisabeth Sparkle was going to be blonde or brunette, it changed who’s going to be Sue. We worked with a US casting director who had gathered ideas for Sue [and they were] mostly newcomers to the industry.

At one point, we were stuck because all my first ideas had been declined, and we still didn’t have any financing. We had some interest, but until we had the cast, no one would really step in. I was working with my producers to gather ideas for Elisabeth Sparkle, and at one point, I said, “We need to send to different actresses who could be potentially interested and go a bit wider in the ideas.” Demi was one, but because we had so many nos from actors who had a strong image, I doubted she would [say yes]. But I said, “We have nothing to lose. Let’s send the script and we’ll see.” When Demi received the script, she loved it and immediately showed interest.

So, we met and, for me, it was more about getting to know her, to feel if she would be willing to take the level of risk that the movie needed. I knew all the challenges that the movie was going to require with the intensity [and] everything that builds the visual world, the mental world. Demi had never done those types of films, so it was for me to explain the way I was working and that the movie was so specific in its vision that she had to be really willing to work with that.

For me, it was important that she knew the practical level of shooting. It was [about] explaining to her the level of prosthetics and the many long hours in the chair. We sometimes had to shoot [out of] chronological order and, on the day, it can be very tiring, very challenging.

A very important element was nudity because nudity was a real tool for me to tell that story. Each shot with nudity had a very strong meaning. It was meant to say something about the character and it was building the story together with the performance. I wanted to be sure that she understood the meaning of it.

Something important to discuss upfront is the conditions of our shooting because we were not a huge Hollywood production. I needed to share with her that [we were shooting] a hundred days in France in an indie way. We’d have the minimum that we’d need to be able to work, there would not be all the Hollywood stuff. Those elements [needed to be] crystal clear for both of us in advance.

All those preliminary conversations made me understand that she really wanted to make the film, she really loved the script and I think she felt like it could be a very important movie. It also made me understand that she was ready to jump into the film.

She offered me her book when we met because it was a great way to get to know her, and her book made me see her in a totally different way. I discovered someone who wanted to get back the narrative of her own life. During her whole career, she navigated her way in a very tough, male-dominated industry. She’d made very risky choices. I discovered someone who has this rock and roll spirit that allows them to jump into different projects. That’s the moment that [made] me feel that she was the right choice for the film.

When I started to feel that Demi was the right choice, I started working more on the Sue parts, where I met Margaret Qualley, among others. That process took us almost a year.

I believe that a movie is the meeting of a script, a director and an actor who meet for a good reason at a certain time. I think Demi was really at that moment of her life to tell the same story as the one I wanted to tell.

Did you just have meetings, or did Demi Moore also work on scenes with you?

Coralie Fargeat – Before I decided to choose her, it was just meetings. We first met in Paris. Then we did a few meetings on Zoom, then we met again. I think it was six meetings before we decided to work together. Then we worked on the film, but it was quite a short prep time. Much of the prosthetic process had to start before she arrived.

When she arrived, we worked on readings of the scenes, on rehearsals for the key scenes that were very technical. The make-up removal scene, for instance, has no dialogue and it’s a sequence almost, so if everything is not at the right level, you have to start all over again. Every little detail in terms of rhythm, framing, and the type of make-up she’s going to apply has a huge importance on the way the scene is going to build, so this is one scene I did in advance to rehearse for the technical details.

[The make-up] scene is made of three beats – when [Demi] starts to do her make-up, then she sees something that stops her, and then she does it again. We needed maybe 15 takes of each beat to arrive at the tone, rhythm, pacing and emotion that was the right one. I remember the final one, which is the one when she really destroyed everything.

It was a very challenging scene because when you apply make-up, remove it, reapply make-up – it’s very tiring for the skin. I remember [Demi] was tired and she said, “I don’t want to go again.” And I told her, “We’re still not there yet. There is some kind of violence that we haven’t achieved.” It was a tiring, challenging day. We all knew this scene was so important, so we were all stressed. She agreed to do that final take, the 15th one, and that’s where she found that moment. She let everything go. If we didn’t have that take, the scene wouldn’t have been at that intensity.

There is a very specific process to know how to push an actor to get to the level of intensity you need. Sometimes, it needs them out of their comfort zone, so always convey why it is important so the actor can understand. That’s what was great with Demi – we have a very different process of working, so it was great to navigate through that together. I think she always trusted the point of view of the director. She’s very smart and very instinctive because she listens to the emotional parts of the project.

What do you think is important when working with the director when it comes to communicating ideas?

Coralie Fargeat – I spent two years writing the script because, for that specific story and movie, it was built in such an intricate way where everything was building the vision. [There were] choices that I knew couldn’t be changed because everything had been developed so precisely for the world that I was building for The Substance, otherwise, it wouldn’t work. I knew that if I started to change things or do things differently, the whole script would be unbalanced. There was no room for adjustment, and that’s why I needed to be sure that the actor we’d work with would understand that.

Each project has its own process. That’s what I love about film – there are no rules, no one process that you should follow. It’s about finding the right process that is good for your movie and way of working because what can be great for one director doesn’t work at all for another one.

I trust my own [process] and find a way to communicate it. Mainly taking time with Demi to really explain to her why it had to be done in a certain way and give her all the tools to make it work for her to [get under] the skin of Elisabeth Sparkle in the way it was written. And the way it was written also goes with the way it is filmed because when I write, I really write. Considering I don’t write a lot of dialogue, it’s everything else that builds a scene. In my films, locations are characters. The sound is a character. The shots where there are no actors and just objects in macro, to me, are characters as well. They build and tell the stories together with the lead performance.

If you read the script, you see that it’s very detailed and very close to what you see on screen. But of course, for the actor inside that very specific vision, it’s a very emotional way of feeling that, of making the heartbeat of the scene. That’s why I knew that the casting process was very important for me because I knew that I wouldn’t rewrite and that I wouldn’t adjust because, for that project, we wouldn’t have words.

The Academy Awards are going to recognise casting for what it is in 2026. Do you think that it’s important for everybody who’s been doing it for so long, and what does it mean? Why did it take so long?

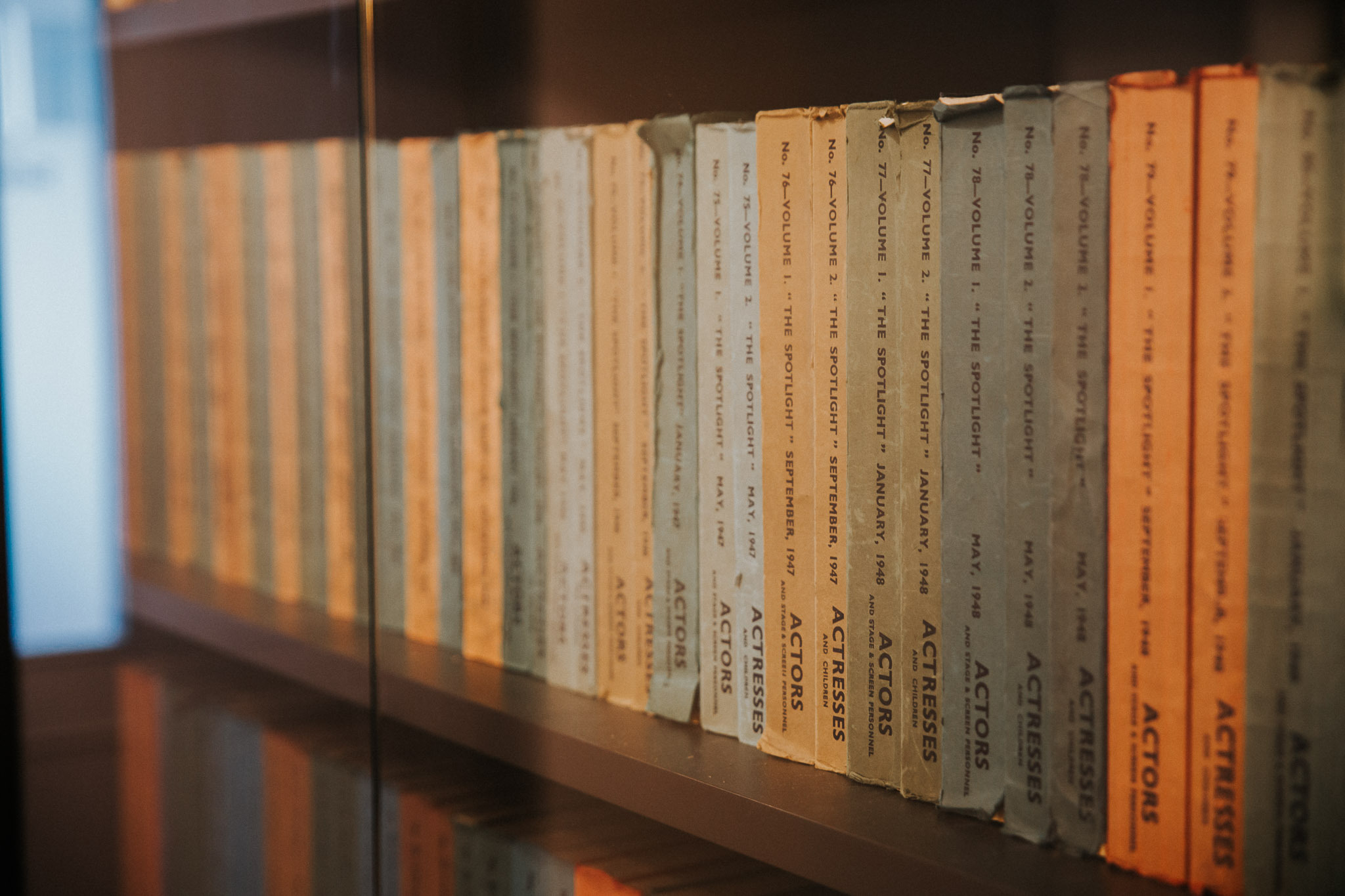

Lana Veenker – As heads of department, casting directors, for a long time, were the only ones who had a main title credit in a film who didn’t have an Oscar category or an award at the European Film Academy or the BAFTAs or anything else. So, it’s been a long time coming – that we have our own award.

We are a predominantly female profession, although we do have some amazing male casting directors in our ranks. But the profession of casting directors started mainly as the producer’s secretary back in the day, at least in the US, and evolved over time into the role that it is today. We’ve struggled for recognition for many, many years. It’s taken a long time for us to finally get this recognition, but I think everyone is really excited and it does mean a lot. There’s now a global movement with the BAFTAs and now the Academy Award and the European Film Academy Award – I think things are changing.

I think Coralie’s film just brings everything to the forefront – about women and how we need to take a look at how society perceives us and what our roles are. I think it’s always good [to] take a look at how people are perceived and what kind of roles they can play. Recognition falls into that category as well.

When you’re thinking about how women are portrayed on screen, do you think now is a good time to show something else, like you did in ‘The Substance’? Do you think we’ll see more of those kinds of roles?

Coralie Fargeat – I hope so. The whole idea of the film is to speak about the place you have in society and representation. To me, everything is linked – the things you see around, the things you grew up with, the representation that you see, what you are allowed to do, not allowed to do, what you are going to claim, what you don’t think you should claim. It has a massive influence on how you take your space in society, or rather how you often can’t take that space.

From a very young age, I’ve been very conscious and shocked by how much boys and girls are educated to take a different place in society. When I grew up, girls were supposed to play with dolls and cooking stuff, while the boys were allowed to go outside and run, be on their bikes and be dirty. All these things say so much about how we are naturally going to think that we’re allowed to behave or not behave, and how loud we are able to be.

I still think that most representation still portrays women in a place that is not as loud as men, that doesn’t take the same space. It was the idea in the film, when ‘Harvey’ comes somewhere, he takes all the space – literally! He enters and eats the frame. I can’t say for people who haven’t seen the movie, but at the very end, the final stage of the character, when she wants to take her place on stage, people don’t let her do that.

When I was writing the movie, when we were trying to get the movie financed, I was hearing things like, “Movies which have female leads don’t make as much money as movies with male leads.” Sad but true. When I hear that, I think it says so much still about the way our society is shaped.

You were talking about casting directors historically being the producer’s secretary. It also says a lot about how the jobs that were done by women were jobs they could do while being at home, taking care of the home, taking care of the kids.

For editors, it was the same. It was mostly a female job because it was a position that allowed you to still take care of your family, be at home and take care of the home because it’s still the truth when you look at the figures. Me, I look at the numbers, things change in society, but the numbers, they don’t lie. And they still show that there is a huge difference about who takes care of the home, of the family, of the kids.

It has a massive impact on how much you invest yourself outside, how much you spend time conquering the world. To me, this is something that has to shift because I think that to be able to invest in the world outside, you shouldn’t be the one who has to take care of everything at home.

Lana Veenker – I was looking at the Gina Davis Institute for Gender Studies statistics and women leads don’t necessarily bring in less money than male leads. It all has to do with the marketing. If they put as much money into the marketing as they do for the male leads, women bring in just as much or if not more than men on those big films.

Coralie Fargeat – I think we can shape the world the way we want, but the will to rebalance things is not there yet. My movie is a feminist movie, it was financed by a studio. They were the ones who allowed us to do the film, so that was really great. But in the end, they didn’t like the film. They decided not to release it. It’s their right to not like the film, but for me, if you want to do something in the world, you should release the movie even if you don’t like it. If you really want to say that those gender things matter to you, you just release those films.

I think the fact that the movie was successful in an economical way was the best gift that the movie can bring to the industry because then you have an example – a movie about women, with a female lead, can gross money. Then, it can help other stories to be made. If you don’t release those films, you cannot create that.

Thanks to Coralie Fargeat, Lana Veenker and Marina Wijn for their time and insightfuls!